Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The Downpatrick and County Down Heritage Railway was just wrapping up its Halloween event last year when volunteers noticed that floodwaters were rising from the nearby River Quoile.

At first, they weren’t overly concerned. “The river rises up and down with the tide,” says chairman Robert Gardiner. “But the amount of rain we were getting was phenomenal.”

The railway station, a volunteer-run Accredited museum with a large collection of operating vintage locomotives, is on higher ground and does not have a history of flooding. But when volunteers went home for the evening, they kept an eye on the remote CCTV. What followed was a night of “doomwatching”, says Gardiner.

As Storm Ciarán raged and the waters continued rising, the team joked darkly that they would have to rebrand as the “heritage canal”. “By the second day, we realised it was a serious incident,” says Gardiner. “But it was too late. The place was cut off and we couldn’t get down there to move anything.”

The museum and parts of its moving collection were flooded, with water six-foot deep along parts of the railway line. Locomotives suffered water damage and the museum lost much of the equipment used to maintain the collection.

By luck, the flood reached only the sub-floor of the station building, sparing the first-floor displays, electrics and plumbing. But the museum has struggled to access government support and has wrangled with loss adjusters.

“We were promised the earth but the pace is ridiculous,” says Gardiner. “You end up on the civil service merry-go-round. Seven months after the flood, we still hadn’t received any direct government support.”

In contrast, the museum has been “gobsmacked” by the response of the local community and wider heritage sector. A fundraising campaign has raised thousands through a range of activities, including a concert held at Down Cathedral over the summer.

Volunteers hope to reopen the museum and parts of the collection this month, almost a year on from the flood. But the clean-up will continue for a long time yet. “The site still feels like a tip,” says Gardiner. “Reopening is only the first step, not the last.”

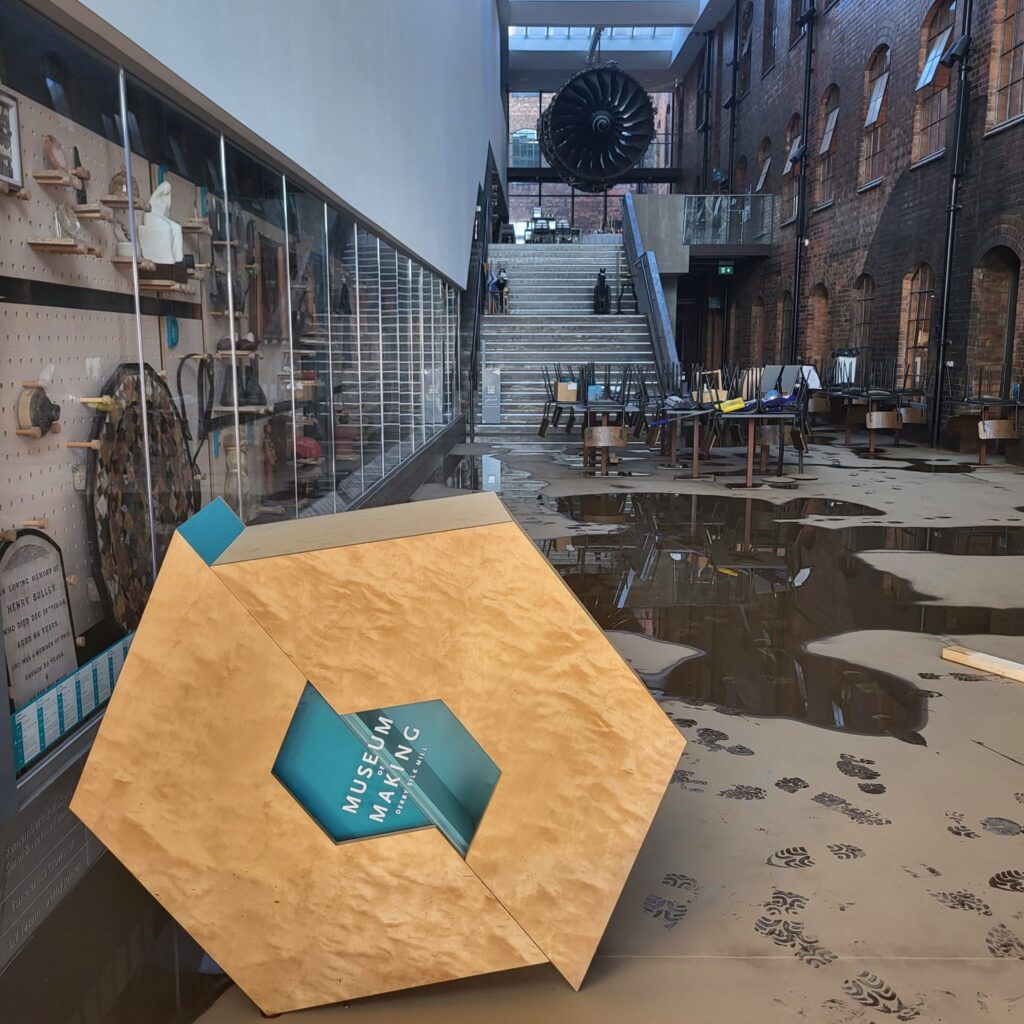

Storm Ciarán was one of a series of storms that hit the British Isles last autumn. The Museum of Making in Derby suffered severe damage following Storm Babet in October. Built beside the River Derwent, the 19th-century former silk mill was designed to withstand an element of flooding and the museum keeps all non-movable collections on the first floor. But the storm exceeded historic levels.

“We imagined that there would be a one-in-15-year flood risk, so that’s what was planned for,” says Tony Butler, the chief executive of Derby Museums Trust. “But the floodwaters were three metres above where they usually are.”

Although the collections were safe, the financial impact of the flood has been significant. A specialist company was brought in to clean away the layers of silt left behind by the floodwater. Lift pit components and fire doors have had to be replaced.

The museum lost laser cutters and a casting furnace in its craft workshop, along with all of its kitchen equipment, which has had a knock-on effect on income generation. It was forced to close for almost two months, missing out on the October half-term and the profitable Christmas period.

The Museum of Making launched a flood-damage appeal and has fared well in accessing emergency support, including council funding and a grant from Arts Council England for costs such as paying casual staff and building storage for sandbags. Its insurance policy covered loss of earnings – but Butler expects that the building will be difficult to insure in future because of the liability.

The wellbeing of staff has also been an important consideration. “It just felt like another thing to have to deal with,” says Butler. “We’ve had plague, pestilence – what’s next? But then we picked up and rallied round.”

Ironically, the experience of Covid has had its benefits; the trust was able to adapt quickly and redeploy staff elsewhere. “People seem pretty experienced now in dealing with changes and unexpected events,” says Butler.

Steve O’Connor, the director of the River & Rowing Museum, which stands next to the River Thames in Henley, agrees. In January, not long after he started in the job, the museum was turned into an island due to flooding caused by Storm Henk.

“I had the experience of leading my last business through the Covid pandemic, so luckily – or not – I’ve had my fair share of crisis management,” he says.

As the museum is housed in a modern building on stilts, it suffered only minor damage, although the car park was left under three feet of water. Nor has it faced any issues with insurance – but only because it’s not covered for floods.

“This is one of the realities of being built on a flood plain, as the premiums we would face are simply not economically viable to put in place,” says O’Connor.

The museum plans to use the experience to spark new conversations with the public about the climate crisis.

The floods suffered by the three museums have been described as “once in a generation”, but as global warming gets worse, incidents of a similar scale are taking place almost annually.

As we move towards another winter, there is a sense that the sector is unprepared for what may come.

Gardiner urges institutions to take pre-emptive action, such as reviewing crisis plans, ensuring there’s a safe place where objects can be moved, and considering scenarios such as what to do if staff are unable to access the site.

“As an Accredited museum, we had a disaster plan, but it was wildly inadequate,” he says. “We had a disaster kit; we found it floating in the floodwater. Imagine the worst-case scenario – and then double it.”

Mitigating against extreme weather

Cultural heritage institutions have made great strides in terms of how they communicate the climate crisis to the public and improve their sustainability.

But running parallel is another urgent – and costly – task: protecting collections, historic buildings and built heritage from the effects of extreme weather.

Across the UK, there is little government support to repair existing problems, let alone to consider preventative adaptation. Sector funders such as the National Lottery Heritage Fund are focused on public-benefit outcomes, making it difficult for climate mitigation projects to meet the criteria.

Balancing the need to adapt to climate change with a remit for historic conservation is also an issue and it can be difficult to navigate planning regulations. And with much of the heritage sector site specific, moving to a safer – or more insurable – site isn’t an option.

Sector bodies are aware of these issues. Historic England is developing a toolkit to help those who manage historic sites to better understand the risks climate change poses.

Many believe it’s time for an urgent conversation with regard to what the sector could ask for at policy level to help mitigate against such disasters.

Derby Museums Trust’s Tony Butler would like to see an initiative similar to the Government Indemnity Scheme that would cover museums and heritage sites unable to access insurance.

There are also calls for a targeted capital fund, similar to England’s Museum Estate and Development Fund, to help museums bring in adaptation and mitigation measures, along with an emergency fund to offer immediate support to cultural heritage institutions affected by extreme weather events.

The heritage railway’s Robert Gardiner believes any measures must be UK-wide. “When you’re talking about damage on a national scale, you need a more joined-up approach,” he says.

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.