Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

Ukraine is fast approaching a grim milestone: the third anniversary of the full-scale Russian invasion that has ravaged the country and shaken the global political order.

In addition to the human toll of the war, which has claimed the lives of up to 100,000 Ukrainian civilians, the cost to the country’s cultural heritage has been devastating. Ukrainians have been clear that they are not just under physical attack: their national and cultural identity is also being systematically targeted.

Anastasiia Cherednychenko, the chair of the International Council of Museums’ (Icom) Ukraine arm, who is leading the Monitoring the Situation of the Moveable Cultural Heritage of Ukraine project, says: “We actually recognise this as a genocide because it’s one of the elements of genocide – first people, then culture.

“For Russians, they want these collections because they want to prove that it’s their history. They don’t only loot museum objects, they also appropriate Ukrainian history. Russia is erasing the history and memory of Ukrainian and national majorities, and the Indigenous peoples of Ukraine as well. They want to prove that it’s Russian territory and that it’s never been Ukraine.”

Russian forces are accused of deliberately bombing culturally significant sites, including built heritage and museums, as well as the mass looting of cultural property. Both constitute war crimes under the Hague Convention of 1954.

The scale of Ukraine’s cultural destruction is difficult to fathom. The country’s authorities say 2,024 cultural institutions have been damaged, with 334 (16.5%) of the country’s cultural facilities destroyed.

Sites targeted include the Unesco-protected historic centre of Lviv, where seven people died and seven cultural monument buildings were damaged in a Russian missile strike last September. Days earlier, the 19th-century Huliaipole Local History Museum had been destroyed by shelling, along with its 18,000 artefacts.

As of 22 January 2025, Unesco had verified damage to 476 cultural heritage sites in Ukraine, including 32 museums and 241 buildings of historical or artistic interest. Ukraine’s culture and tourism industries have accumulated losses of $19.6bn since the beginning of the war.

Over the past three years, Ukrainian authorities say the Kremlin has established a sophisticated looting “network” to transfer thousands of museum objects to Russian territory.

Although the true number is impossible to calculate, hundreds of thousands of artefacts are believed to have been stolen from more than 40 museums in occupied or formerly occupied territories.

Just before the city of Kherson was liberated by Ukrainian forces in November 2022, Russian troops removed entire collections from the Kherson Art Museum, Kherson Regional Museum and the national archives of the region. Staff from the city’s museums have described scouring Russian websites and social media for evidence of where the stolen collections are now.

Russian-affiliated cultural institutions and museum professionals are accused of playing a key role in the looting operation. It is believed that many of Kherson Art Gallery’s 11,000 missing pieces are now stored at the Central Museum of Tavrida in Simferopol, whose director, Andrei Vitalievich Maglin, was sanctioned by the EU and Switzerland last year.

This has raised difficult questions for international museums that still maintain partnerships with Russia. In one controversial diplomatic incident, Icom chose to cancel a conference in Norway last year after a committee member of Icom-Russia was refused entry to the country. Icom-Ukraine said it was deeply concerned by this decision from its parent organisation.

Cherednychenko believes it’s a risk to continue working with the Russian museum sector. “When we communicate with our international colleagues, we try to say to them that it’s dangerous to collaborate with Russian professionals, not only because of the war, but because they collaborate with the Russian secret services,” she says.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture and Information Policy is creating a register to document the available information about works of art found in the occupied territories and to help track down cultural property.

No matter how the war ends, the country will face an uphill struggle to retrieve its stolen heritage. In 2023, the Kremlin amended museum legislation to integrate Ukrainian museums into the Russian network, in effect prohibiting the return of looted Ukrainian artefacts.

“This move, in effect, legalises wartime looting and prevents Ukraine from tracing and returning its stolen heritage,” says Anastasia Serha of Ukraine’s PR Army, a non-profit organisation of communication experts working to document the war.

This legislation was enacted in response to the Scythian gold dispute, which saw the Netherlands refuse to return 565 golden artefacts to Crimea following Russia’s annexation of the region in 2014. After a decade-long legal battle with Russia, the court ruled in 2023 that the objects should be returned to Ukraine.

Museums are also being used as a military propaganda tool for the Kremlin. In Mariupol, which is under Russian occupation, a multimedia museum has opened to tell the story of the city’s so-called “liberation” from Ukrainian “Nazi occupation”.

Last September, the Kremlin also unveiled a new strategy for a “state cultural policy” that Ukraine says is designed to weaponise cultural institutions in occupied regions.

The legislation proposes the full integration of the occupied areas of Ukraine into the “Russian cultural and humanitarian space” by 2030, and outlines plans to use museums, cultural facilities and schools to achieve this.

In the face of these overwhelming challenges, Ukrainians are fighting hard to keep their culture alive. Museum and heritage workers are caring for evacuated or hidden collections, and even under immense strain, they are continuing to engage with the public, particularly children and teenagers, and help people find ways to process the war through culture. With heritage as a target, working in this area is a hazardous job, even for those far away from the frontline.

“The museum staff of Ukraine live in and work in very dangerous conditions,” says Cherednychenko. “Colleagues have been killed by missile strikes on their museums.”

Many heritage workers have joined the Ukrainian army, leaving cultural institutions mostly staffed by those unable to join in combat. They are surviving on painfully small salaries provided by the state, which has been forced to cut funding for culture and museums.

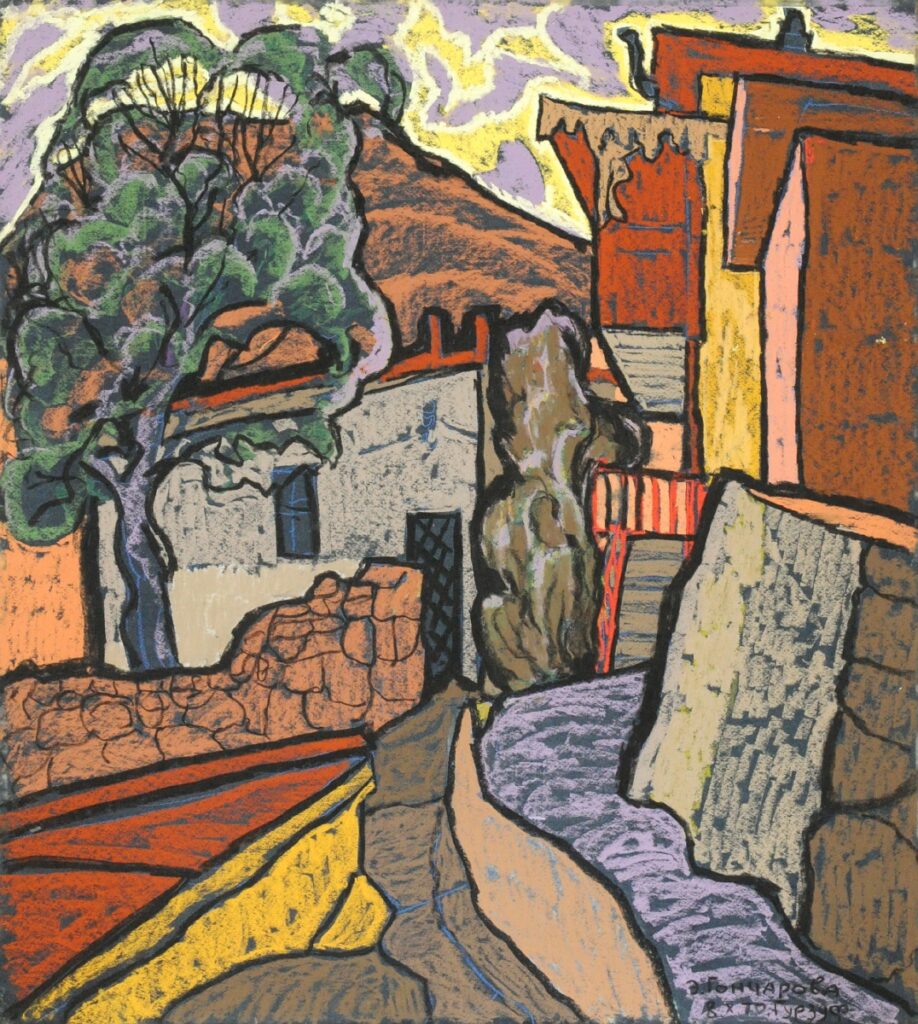

Ukrainians have found creative ways to highlight the theft of their culture. Fashion brand Oliz has produced a Stolen Art collection of silk shawls featuring prints of looted or destroyed artworks, with sale proceeds going to the country’s reconstruction.

The collection features well-loved Ukrainian masterpieces including a piece by the 20th-century folk artist Polina Rayko, much of whose work was lost for ever when the museum dedicated to her was destroyed in 2023.

Creative professionals are also contributing to reconstruction efforts. Livyj Bereh, a volunteer group established in Kyiv by three friends– a multimedia artist, a construction worker and a florist – has helped to restore more than 300 roofs on homes, community buildings and schools. The group was recently awarded the Royal Academy’s Dorfman Prize, which champions new talent in architecture.

In the UK, Ukrainian museum professionals have been working with the Museums Association (MA), Icom-UK and Icom-Ukraine to produce decolonisation guidelines.

Due to launch in spring 2025, these aim to help cultural heritage professionals around the world to be more nuanced in cataloguing, labelling and contextualising the country’s history and heritage in their collections.

The targeting of Ukraine’s heritage raises questions about the protection of cultural heritage and identity in a new age of global turbulence; in the three years since the conflict began, similar levels of cultural destruction have been seen in Gaza and Sudan.

Cherednychenko says museums in the west need to start being honest with their audiences about how the world has changed.

“For international colleagues, maybe it’s time to talk to visitors to explain what is going on, not just in Ukraine but around the world,” she says. “We are just one piece of the puzzle. Many countries try to live as if nothing has changed, but the world order from the second world war is broken – it’s gone.”

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

You must be signed in to post a comment.

We should be raging against the misappropriation of culture by Russia and other countries.