Enjoy this article?

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The recent news that psychiatrists in Brussels are prescribing free museum visits indicates a growing awareness of how the arts could offer targeted support to people experiencing mental health difficulties.

But in the UK, it’s an under-developed area, according to the Creatively Minded at the Museum report produced by the Baring Foundation with the Museums Association. The report notes that while museums are seeking to become more accessible, “when it comes to applying these principles to people living with mental health problems, there has been much less consistent and concerted effort than for, say, working with people living with dementia”.

The report suggests that “projectitis” might be a factor, with mental health-related work often dependent on particular staff members or grants. But the document’s 16 case studies, including three specialist mental health museums and 12 other museums ranging from local institutions to national art collections, nonetheless highlight the potential for this area of work.

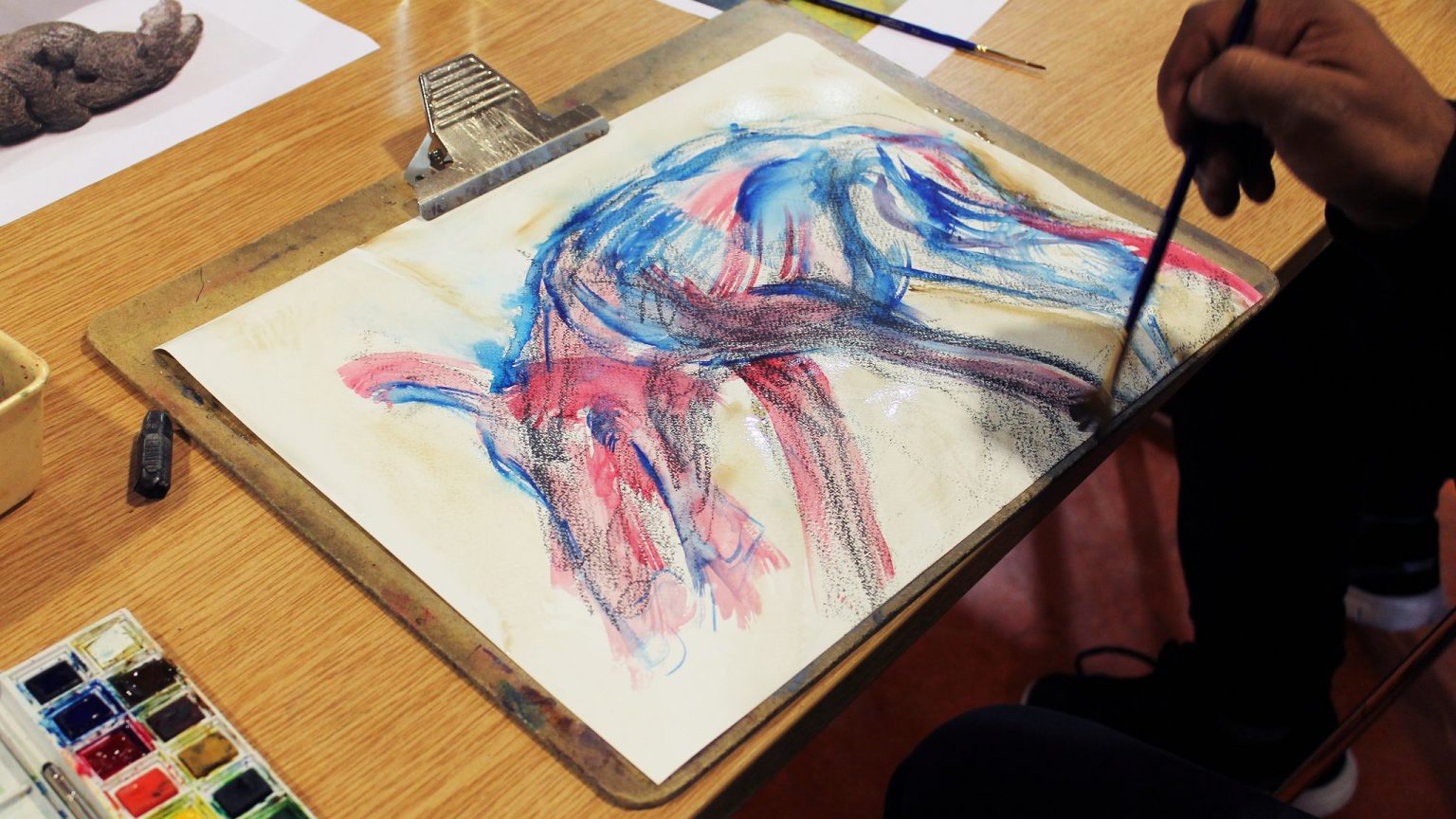

Many of the featured museums capitalise on the unique nature of their spaces. Since 2013, for example, National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) has worked with homelessness charity Rowan Alba – currently through monthly artist-led sessions with people who have lived experience of alcohol-related harm. Rowan Alba clients and volunteers visit an NGS exhibition and then take part in a practical art session, with lunch provided.

In the report, NGS’s head of learning and engagement, Siobhan McConnachie, notes Rowan Alba’s feedback that the gallery environment is an uplifting place to meet, and is free and easily accessible. The chance for visitors to move about as they wish also makes it the opposite of negative, intense clinical settings.

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

One client said the sessions allowed them “to be somewhere, where there are many people around, and not have to interact with them – I didn’t think such places existed”.

“Rowan Alba discovered all sorts about the clients they were working with, that we wouldn’t have otherwise known,” says McConnachie. “It adds that human engagement level with somebody with whom you may be dealing on a health-related or a social-related matter. You start to see the full person because they’re bringing more than just that issue to the conversation.”

The Lightbox gallery in Woking has worked with Woking Mind (which recently became part of the charity Catalyst) to provide relaxed tours for people with a range of mental health problems. Heather Thomas, the museum’s head of learning and engagement, says participants enjoy learning new things, from local history to gossip about artists’ lives. She says: “Wellbeing is all about connecting and learning, and seeing something that you enjoy.”

A few projects featured in the report put museum resources to work in mental healthcare settings. During Covid lockdowns, the Beaney House of Art and Knowledge in Canterbury worked with Kent and Medway Partnership NHS Trust’s psychology teams to loan object handling boxes to hospital wards.

Over 12 months, this led to 1,800 engagements across six wards. Patients who didn’t usually get involved with ward activities participated in the sessions. Canterbury Museums and Galleries’ health and wellbeing coordinator Jemma Channing says some started asking for specific loan boxes covering different periods of history.

The Beaney included contributions from some of these patients in an exhibition on mental health, A Place of Safety, held this year. Facilitated sessions with objects prompted them to create poetry, paintings, drawings and lanterns that were then displayed in the exhibition.

A different approach taken by some museums is offering paid training placements. Since 2017, London’s Foundling Museum has run paid five-month placements for those who have spent time in care between the ages of 18 and 26. This helps participants develop creative and life skills through activities such as delivering family workshops, which they can continue after completing the post.

Elsewhere, Dulwich Picture Gallery worked with South London and Maudsley Mental Health Trust Recovery College to pilot six-month placements to train five creative peer facilitators (aged 18-25), who co-designed and co-delivered creativity and wellbeing workshops for schools.

Evidence suggests that such initiatives often have a positive impact on participants’ wellbeing. The Foundling’s most recent evaluation revealed that two-third of trainees “had gained a new sense of self-belief and self-confidence”. And in a community engagement programme run by Bath’s Holburne Museum for people with lived experience of mental health issues and social isolation, 73% of those who had attended a group for six weeks or more said it “had positively affected their wellbeing and quality of life”.

Many of the museums describe how the work also benefited them, by deepening their understanding of collections, enabling co-curation of exhibitions and supporting the inclusion of a wider range of voices.

But despite this success, the number of initiatives appears limited across the sector. To move things forward, the document makes eight recommendations, including the need for explicit recognition that “this is an important area which is currently under-developed”. It also urges museums to initiate partnerships with the NHS and the voluntary sector, and consider relevant training for staff.

Thomas agrees that training, such as in mental health first aid, is useful, as it gives staff the skills and confidence to manage issues that may arise. She says effective communication is also essential to determine what participants actually need.

“Starting from what they want, rather than what you think that they might want, is key,” says Thomas. For example, when planning the Open Mind tours, the gallery suggested workshops, but the charity said tours would be better because many clients didn’t often have the chance to visit exhibitions.

McConnachie says building trust through sustained regular collaboration is important to help develop a shared understanding of what each partner can contribute. Then once you have that trust and experience, people start to see other opportunities.

For example, following on from NGS’s work with Rowan Alba, two networking and partnership sessions involving many other community health providers have been held at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

“This might now take us in a direction where we start to host regular sessions, where partners can come together and experience for themselves what an art gallery can give, as well as understand how they could work with each other,” says McConnachie.

Funding is vital to support this area of work. In the report’s recommendations, funders are asked to make clear the relevance of their funding to this work and consider offering dedicated pots.

But McConnachie stresses that it is not just about the amount of money, but also having a funding structure that can support an ongoing evolution of work responding to specific local needs. She says NGS’s work with Rowan Alba “started as a one-off project, and has since become a multi-year ongoing programme that can go in a number of directions”.

Leadership and sharing good practice in the sector are other important factors highlighted by the report. It recommends more showcasing events, such as those run by the Holburne in Bath. And it argues that “a museum should take a leadership position in this area in the way that New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art did for work with people living with dementia”.

The report highlights the imaginative role that London’s Wellcome Collection has played in developing conversations around mental health. The report’s foreword is written by Dolly Sen, an artist and writer who has worked on various projects with the Wellcome, including a performance held last October that responded to studying the institution’s psychiatric archives.

The Wellcome Trust, which oversees the Wellcome Collection, recently launched Mindscapes, a year-long cultural programme bringing together diverse approaches to understanding mental health, including policy, culture and communities. Working with other major institutions, the project will include artist residencies, a crowd-sourced documentary, exhibitions and community events in cities around the world.

Danielle Olsen, cultural partnerships lead at the Wellcome Trust, says “cultural venues can provide safe spaces that allow visitors to explore the various – and sometimes difficult – themes of mental health in more detail”. She argues that involvement in Mindscapes, whether as researcher, creative or audience member, “has the potential to change attitudes towards mental health through a broadening and deepening of perspectives”.

The Wellcome’s medical collections lend themselves to the topic, but this work is not dependent on a museum’s subject matter. The report says: “Any museum can choose to engage with people with mental health problems – it’s a question of attitude and interest.”

Jonathan Knott is a freelance writer

The report’s recommendations

- There needs to be explicit recognition by individual institutions and infrastructure bodies with an interest in the museum sector that this is an important area that is currently underdeveloped.

- Valuing the lived experience and leadership of people with mental health problems, both staff and community members, is essential to developing work in this area.

- Museums should proactively reach out to the local NHS and voluntary sector bodies such as Mind to consider areas for collaboration.

- As a minimum, museums should ensure that relevant activities and displays are available for Mental health Awareness Week and World Mental Health Day.

- Museums should consider training for staff such as Mental Health First Aid Training or Trauma Informed Practice, especially for learning and engagement staff.

- More showcasing events, such as those run by the Holburne Museum in Bath, are needed to share good practice and increase visibility, along with more online guidance tools.

- A museum should take a leadership position in this area in the way that the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York did for work with people living with dementia.

- Museum funders should make clear the relevance of their funding for this work, or offer dedicated funding pots.

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.