Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

Appearances can be deceptive in the realm of fortified collections. Take, for example, the menacing edifice atop Galahill in the bonnie borders town of Jedburgh.

There’s a steep climb up to the commanding crenellations, towers and gatehouse. It certainly looks like a castle and has the intimidating feel and damp-stone mustiness of a castle.

But the original town fortress was demolished in the 15th century following its frontline role in the battles for Scottish independence. The building that stands there now is the old town jail, built to look menacingly medieval in the 1820s, and which now houses the museum that tells the tales of local crime and punishment.

“Jedburgh Castle Jail and Museum is a quirky building,” says curator Shona Sinclair. “In other museums, you’ll have keypads at every door, but here we have huge bunches of keys so you have to be prepared to learn how to get around.

“Our front-of-house staff can feel the cold sometimes and the thick walls mean the wifi is poor,” says Sinclair, who often feels the chill of the spooky environment.

“Tech doesn’t work very well and batteries drain quickly in certain areas. Being a keyholder, I have to come out in the middle of the night if an alarm sounds and it’s a creepy experience if you let your imagination run riot.”

The lure of the paranormal is, however, a moneyspinner for the museum as hordes of ghosthunters armed with microphones and monitors spend their Saturday nights wondering: “Is anybody there?”

“They keep coming back so they must be satisfied, and some say they have heard bagpipes on the battlements,” says Sinclair. After the winter closure, she leads the museum’s annual spring clean.

“It deteriorates and crumbles and there’s a lot of dust. Other museums can take displays down and put them away safely but even if we put things in cases, they are still affected. Maintaining the perfect environment for our objects is very intensive.”

One of the cell blocks has been kept in its original state to provide visitors with a scarily immersive experience, she adds. “There are stories about young children locked up for three days for stealing turnips from the field, cases of vagrancy and petty theft by women and even executions carried out on the site.”

Visitors also have to have their wits about them as they make their way around the castle. “Access is a challenge with spiral staircases and uneven floors. Coach trips are especially nightmarish; you just can’t get the buses up the hill,” says Sinclair.

The flexing of military muscle plays a part in the story of Carisbrooke Castle, which has dominated the skyline in the middle of the Isle of Wight for centuries.

“The building dates back to the Norman Conquest and has been through many iterations, which is what makes it so interesting,” says manager Virgil Philpott.

“It saw action on just one occasion when it was besieged by the French in 1377. That ended when their commander was killed by crossbow-fire from the battlements.

“Most famously, the castle was used as secure accommodation for King Charles I after the civil war. He thought he would come here and negotiate his freedom, but he was kept here until his trial.”

An escape was attempted one night in March 1648 when the king planned to lower himself 10ft down into the courtyard via a silk cord, only to embarrassingly become stuck in the window frame.

“The castle later fell into disrepair and eventually became something of a folly,” says Philpott. “We have paintings, including one by 19th-century artist JMW Turner, depicting the place as a romantic ruin.

“I was walking with a volunteer when he pointed to one area and said: ‘The fireplace that came out of that room is now in my gran’s house.’ During the 19th century, the place was left unattended and islanders took stones and bits and pieces for their homes.”

After some restoration, the castle museum was set up 125 years ago by Princess Beatrice, Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter who was governor of the Isle of Wight from 1896 until her death in 1944.

It’s the Charles connection, however, that keeps the punters coming to Carisbrooke.

“Last year, someone turned up looking for details about an ancestor who was part of the king’s retinue. Later the same week, a different person came in asking about the same ancestor. We were able to connect two distant relatives who had never met,” says Philpott, who is himself intrigued by some of the museum’s Charles-related memorabilia.

“We have some coded letters he wrote to supporters when he was planning his escape missions, one of which still hasn’t been properly decrypted, which I think is fascinating,” he says.

The museum also showcases the different collecting policies of curators keen on recording the island’s social history.

“If something had Isle of Wight provenance, the museum kept it,” says Philpott, adding that as a result, every available space in the castle is packed with stored objects.

“We work out of the governor’s mansion, but all around us there are walls and high windows, perilous staircases, and slippery and dangerous floors. We have a constant battle with mould and damp, but you have to work with what you’ve got and be very inventive about how you manage things,” says Philpott, who finds one particular piece of local history rather intriguing.

“There was an Isle of Wight brickmaking family, one of whom obviously fancied himself as an artist because he fashioned a brick sculpture featuring the face of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler grafted on to the body of an eagle feasting on the corpse of Poland.

“It is, to say the least, remarkable, but it represents an island tradition and is obviously an object of its time. When the regional board of the arts council came here for a meeting, they were fascinated by it.”

At Enniskillen Castle on Lough Erne in Northern Ireland, visitors can soak up the history of six historical buildings, and are encouraged to take advantage of the location’s extensive grounds, which host a range of activities and provide stunning views of the island town.

“Our spaces can be hired for a variety of events from outdoor theatre, community days and international food and craft markets to music festivals and wedding ceremonies in the castle garden,” says Sarah McHugh, museum and heritage officer at Fermanagh and Omagh District Council.

“As a significant local landmark close to the border with the Republic of Ireland, it’s important that we strive to be inclusive, welcoming people from all communities, abilities and faiths,” she adds.

The 600-year-old castle houses both the Fermanagh County Museum and the Inniskillings Museum, which is run by the Ministry of Defence Charitable Trust.

Through displays and hands-on activities, the former explores the area's history back to the days of Gaelic chieftain Hugh “the hospitable” Maguire, offering the chance for Maguires from all over the world to reconnect with their ancestors.

“The castle complex has developed over the years to include a range of buildings representing diverse histories, from medieval stronghold and 17th-century plantation [colonisation] castle to later garrison fort,” says McHugh.

“The keep features the last remaining medieval part of the castle and has been besieged, burnt down and rebuilt [during] its history.”

As the island became embroiled in the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries, County Fermanagh’s geopolitical position became ever more significant, says McHugh.

“The Inniskillings Museum galleries house a rich collection of personal treasures and battlefield curios telling the story of the town’s two regiments – the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers [infantry] and 5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards [cavalry] – from their origins in 1688-89 up to their respective amalgamations,” McHugh says.

When Richard Gough sets off to work in the morning, his children sometimes jokingly refer to him as “the king of the castle”.

There are certainly less-impressive commutes than the climb up to Shropshire’s Shrewsbury Castle, the fortress that was the last line of local defence during the Anglo-Welsh battles of the 13th century and the parliamentary sieges of the English civil wars some 400 years later.

“Once you’ve passed through the castellations, the inside has the charm of the private house it later became,” says Gough, director of the Soldiers of Shropshire Museum, which moved to the castle in 1985.

That’s down to the late 18th-century improvements made by the county surveyor, one Thomas Telford, the Scottish civil engineer and first president of the Institution of Civil Engineers, who set about restoring the interiors to a blueprint by the architect and designer Robert Adam.

“There’s a magnificent parlour upstairs, and downstairs there’s a perfectly circular room – even the doors are curved on a radius – which we use for weddings, and weapon demonstrations,” says Gough, who adds that the history of the place can be both a blessing and a curse for the museum.

“We have issues with covenants and restrictions of the listed status,” he says. “It’s not like a traditional museum where you can knock a nail into a wall with impunity. We have to put a lot of thought into designing things that don’t affect the fabric.

“That, of course, means the cost of repairs is quite high; last year, we repaired a downspout on the guttering and it took an army of people, including a blacksmith to make the right brackets, which just adds layers of complexity.”

On the plus side, he adds, the building has the prestige that a military museum needs.

“These days, many museums talk about moving into derelict places or abandoned high street shops, which is a great idea as you shouldn’t be limited by what the building looks like. I feel, however, that military museums really do need the stature of grand buildings, and I’ve always thought that soldiers and their stories belong in castles. Our county reservists certainly see this place as their home.”

Visitors flock to find out how their ancestors contributed to world history through military operations, adds Gough.

“With what’s happening currently in Palestine and Ukraine, increasing numbers want to know how we fit into the global picture as a military nation and, predominantly, a postwar peacekeeper. People are looking for connections and confirmation that the British army has done good things.”

Curios in the collections include a lock of Napoleon’s hair that the former French emperor gave as a token of respect to Captain Thomas Poppleton of Shropshire’s 53rd Regiment of Foot 2nd Battalion, who had guarded the Frenchman during his exile on the Atlantic island of St Helena in 1817.

“Our county regiments fought in the Peninsular War and we have many, many objects from it, but the hair is a real bonus that rounds off the story,” he says.

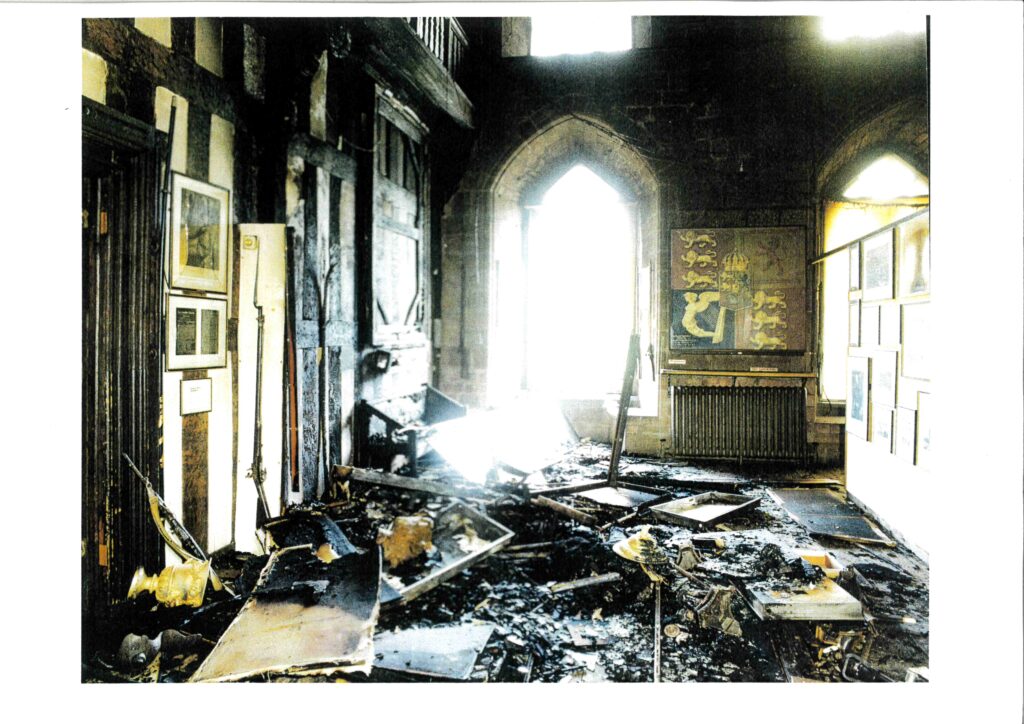

Another display recalls a more recent event much closer to home – the firebombing of the castle and museum by the Provisional IRA in 1992, which caused significant damage although no one was injured.

“People are surprised to see it as they don’t remember the incident, but it’s a story worth telling as we’re the only mainland military museum to have experienced a terrorist attack,” says Gough.

“In a perverse way, we have that to thank for our renewed displays and reinvigorated museum, now much stronger since it has been repaired. That’s another benefit of being in a castle – it’s pretty strong and secure.”

Gough says the biggest challenge the museum now faces is the expiration of its lease with the local council in 2027.

“We have to persuade them we are worthy of the building and that we can be viable and relevant in years to come,” he says. “With changing tastes and financial pressures, I can see how they might think they could install someone here who could earn them a lot more than we do.”

John Holt is a freelance writer

The dramatic edifice of Jedburgh’s former town jail, built on top of Galahill in the 1820s, now houses Jedburgh Castle Jail and Museum, Scotland. Visitors can get a glimpse of life inside and hear stories about the inmates. Cell Block III is where male debtors and female prisoners were kept – originally separated by a wall.

This stronghold on the Isle of Wight dates back to the Norman Conquest, but its most famous visitor was King Charles I. During the civil war, the king was held here as a prisoner between 1647-48, as depicted in this engraving until his trial and execution in London. “The castle fell into disrepair and became something of a folly,” says manager Virgil Philpott.

About 125 years ago, Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice, who was governor of the island, set up the museum. Today, the collection includes artefacts that chart the island’s social history as well as that of the castle.

Carisbrooke, which is managed by English Heritage, attracted 110,727 visitors in 2023, according to Association of Leading Visitor Attractions figures.

Located on Lough Erne in Northern Ireland, Enniskillen was built nearly 600 years ago by the Maguire clan. Its strategic position guarding one of the few passes to Ulster saw it subsequently used as an English garrison fort in the 17th century.

“As a significant local landmark close to the border with the Republic of Ireland, it’s important to be inclusive,” says Sarah McHugh, museum and heritage officer at Fermanagh and Omagh District Council.

Today, visitors flock to see the Fermanagh County Museum and the Inniskillings Museum as well as events such as The Maguire House Party.

Shrewsbury Castle in a 19th century engraving) is now home to the Soldiers of Shropshire Museum, a collection of military memorabilia that draws visitors wanting to find out how their ancestors contributed to history.

“People are looking for connections and confirmation that the British army has done good things,” says director Richard Gough.

Among the more interesting curios is a lock of former French emperor Napoleon’s hair, gifted by him to the British captain who guarded him when in exile on St Helena.

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

You must be signed in to post a comment.

Pity you missed out Tamworth Castle, an imposing Norman motte and bailey castle that sits in the town centre, intended to impress the status of the landowners on the resident serfs and inhabitants of the town! The serfs were likely forced to build the motte on which it stands, second only in size to Windsor Castle. Tamworth Castle appears small from the outside, but visitors frequently remark on how much there is to see and do inside, and how Tardis-like it is inside with fifteen rooms open to the public. The same issues apply however, as with the other castles, access up a steep slope, lots of creaky uneven stairs, thick walls making it cool in summer and cold in winter, maintaining the environment and getting exhibits in and out of the Castle is a nightmare, as the slope is the only way in and out. However, the awards and the accolades that Tamworth Castle holds make it well worth a visit, and many visitors return again and again for different events.