Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The Turner Prize recently celebrated its 40th anniversary, with the winner of the latest award announced on 3 December at a ceremony at Tate Britain.

But as the prize enters middle-aged respectability, what does the future hold for what was once the UK’s most notorious art award. Is it still relevant and does it matter that it doesn’t seem to have the same capacity to shock and provoke as it once used to?

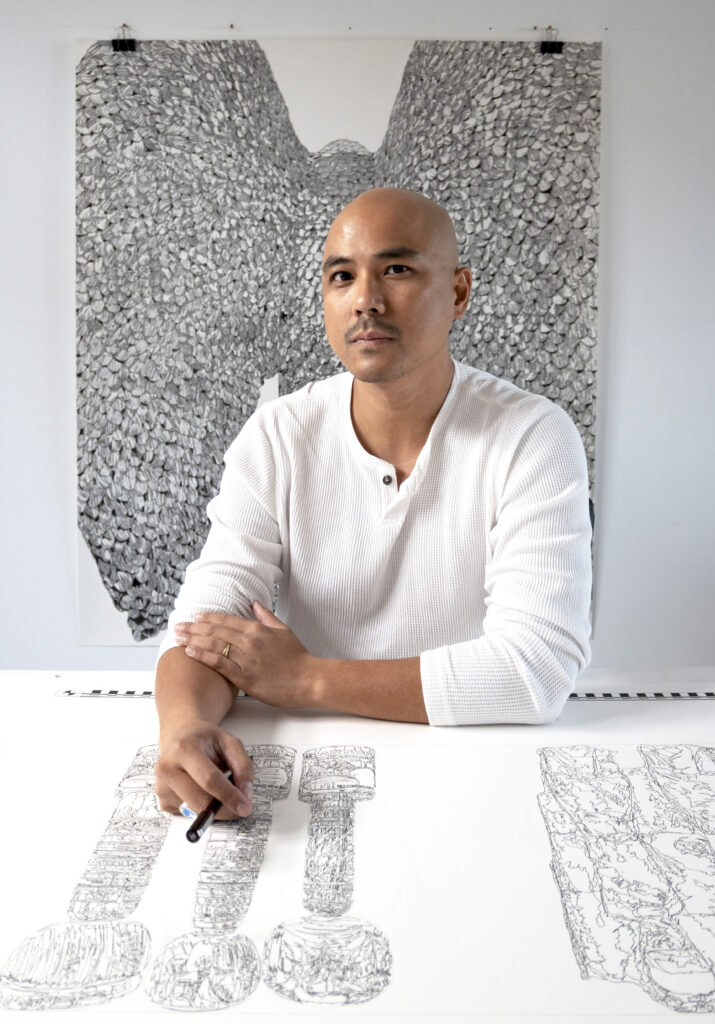

Having said that, last year’s edition – on display at Tate Britain until 16 February and featuring work by nominees Delaine Le Bas, Pio Abad, Jasleen Kaur and Claudette Johnson – has managed to garner headlines, split the critics and create debate about not only the merits of contemporary art, but of the prize itself.

“At 40, the Turner is knackered, creaking and past it… Time to revamp this sorry embarrassment of a prize or retire it completely,” writes Laura Freeman, chief art critic at the Times.

Other journalists disagree, reflecting the prize’s ability to stoke wildly differing opinion. “It’s a show that feels as if it actually has a finger on the pulse of 2024,” says arts writer Waldemar Januszczak in the Sunday Times.

Alan Bowness, former Tate director, established the Turner Prize in 1984 to “help draw greater public discussion to new art, in much the same way as the Booker Prize has helped the novel”, he said.

The fledgling award was backed by the Patrons of New Art, a group of private individuals and patrons formed in 1982 to promote contemporary art at the Tate Gallery.

But the early years were not a success. Art critic Ben Luke, who used to work at the ate in communications, outlines in the Art Newspaper how the prize was derided at the start: “It was, for the first few years of its existence, both a mess and a flop. The critics hated it, artists seemed embarrassed by its existence, and initially they were given hardly any notice and very little exhibition space to show their work to a bemused public.”

In 1991 the prize was revived, with new sponsorship from Channel 4 driven by Januszczak, then the TV station’s head of arts. Luke points out that the new format comprised a tight four-artist shortlist, an increase in the prize money and, crucially, a proper exhibition in the Tate’s best galleries.

The Turner Prize brand, linked to the punkish and provocative Young British Artists of the 1990s, became fashionable. Indeed, “the annual tussle for the Turner Prize – a sort of blood sport-cum-pantomime, amped up by the tabloids – was how most of the public engaged with contemporary art’s provocative goings-on,” writes Alastair Sooke in the Telegraph.

Some artists were particularly controversial, keeping the prize in the public eye. Tracey Emin’s work My Bed, shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1998, is a pre-millennium cultural marker, while another contentious installation from 2001, Work No. 227: The Lights Going On and Off, by Martin Creed – an empty room lit up for five seconds and then plunged into darkness for five seconds ad infinitum – also symbolised the prize’s conceptual clout, confusing and gratifying visitors in equal measure.

Arts writer and curator Andrew Renton, who is a professor at Goldsmiths and was a judge in 2006, describes how the prize seeped into the public consciousness: “It was sometimes stressful being put on the spot about your decisions. Taxi drivers always want to talk about the Turner Prize. But how great that they are aware of it.”

Along the way, the prize has, at key moments, also reflected social and political trends. In 1997, the first all-female shortlist in the prize’s history – featuring Cornelia Parker and the winner, Gillian Wearing – prompted accusations of political correctness (it remains the only all-women list so far). In 2021, five artist collectives battled it out, a move sparked by the lack of eligible shows staged during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Touring the Turner Prize to key regional galleries has also changed how the prize is perceived, widening the platform to new audiences. In 2007, it was held outside London for the first time, heading to Tate Liverpool where it helped to celebrate the city as European Capital of Culture 2008. And in 2011, the prize show proved a huge draw at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead when the venue drew 149,800 visitors.

In 2023, the Towner Eastbourne gallery capitalised on the chance to take on the Turner, making the prize a key strand of the town’s Eastbourne Alive arts programme.

Hosting the award served as a “powerful catalyst for change” for both Towner and Eastbourne, delivering an additional economic impact of £16m and driving a 25% uplift in tourism, says Joe Hill, the director of the Towner Eastbourne.

Crucially, more than 65% of young participants in the Eastbourne Alive programme indicated they were more likely to pursue a creative career, Hill adds.

But some artists and critics have not always welcomed the move to cast the net wider, claiming that the nomadic prize exhibitions are a misstep.

“All [iterations outside London] featured the Turner being used clunkily as a travelling propaganda tool seeking to inculcate a wider British public with patronising Tate notions of the value of contemporary art,” writes Januszczak.

The most far-reaching change came in 2017 when the age limit of 50 for shortlisted artists, established in 1991, was abolished. “Januszczak and [former Tate director Nicholas] Serota’s formula ensured that the Turner Prize could thrive by tapping into the energy of an emerging generation in the 1990s. And the numbers bear this out,” writes Ben Luke.

“Between 1984 and 1989, of 37 shortlisted artists or collaborative duos… many had long-established international reputations and 10 were aged over 50. But in the first decade of the new format [from 1991], just seven of the 40 artists or duos shortlisted were over 40.”

That decade is seen as the prize’s heyday, when Rachel Whiteread, Damien Hirst, Chris Ofili and Steve McQueen were among the winners, Luke adds.

Alex Farquharson, Tate Britain director, defended the rule-change in 2017 by emphasising that the Turner Prize has always championed emerging artists.

“It has never been a prize for long service but for a memorable presentation of work in that year,” he says. “Now that its reputation is so firmly established, we want to acknowledge the fact that artists can experience a breakthrough in their work at any stage.”

Lubaina Himid was 62 when she won the Turner Prize in 2017 under the new criteria. She has mixed feelings, though, about clinching the prize. “For me the change of rules was lucky in the sense that it gave me the opportunity to be nominated, shortlisted and then win,” Himid says.

“However, this left me open to being defined by my age and of being accused of simply winning as a mark of respect for ‘long service’, which was sickening really.”

She points out that Naming the Money, which was cited in the Turner Prize nomination, was commissioned for a show at Newcastle’s Hatton Gallery in 2004 when she was under 50. The piece, which explores identity and race, was shown again at Spike Island in Bristol in 2017.

“Older artists definitely benefit; for a start it is useful to know that thousands more people will want and be able to see the work I make because curators want to include it in major exhibitions,” Himid says. “Winning at 40 is better than at 50 or 60, but being able to reach so many people even late in life is something to be treasured.”

Other nominated artists have conflicting feelings. Jeremy Deller, who triumphed in 2004, says: “It was enjoyable, almost fun. I just tried to get as much out of it as possible.”

Dexter Dalwood, a nominee in 2010, says many people suddenly became aware of his work outside of the art world so “it was like putting your head above the parapet”. But Heather Phillipson says of her experience in 2022: “I’d prefer never to think of the Turner Prize again.”

The prize always faces challenges, especially in finding on-brand corporate sponsorship. In 2019, the coach operator Stagecoach South East was dropped as a sponsor of the prize show at Turner Contemporary in Margate after it emerged that Brian Souter, the chairman of the firm’s parent company, had campaigned against gay rights.

For the 2024 prize, the winner received £25,000; each of the other three shortlisted artists received £10,000. The charitable foundation set up by Lord Browne of Madingley provided £15,000 to the total funding pot, while the Uggla Family Foundation established by Lance Uggla – a trustee of the Tate Foundation – also gave £15,000. The foundation established by Browne, former chief executive of the controversial oil company BP, sponsored the prize in 2019.

Previous high-profile sponsors have included Gordon’s Gin and the French banking group BNP Paribas, prompting the Times to report last year that “the Turner Prize has attracted only £30,000 in sponsorship, raising questions about levels of interest in the long-standing contemporary art award”.

BNP Paribas says it has no plans to sponsor the prize again; Gordon’s Gin did not respond to a request for comment.

Another difficult moment came in 2022 when Laura Cumming, the art critic of the Observer newspaper, highlighted “apparent conflicts of interest”, describing how three of the six jurors were in charge of galleries where the shortlisted shows took place (the oldest-ever winner at 66, Veronica Ryan, was shortlisted for her exhibition at Spike Island in Bristol, whose director,

Robert Leckie, was one of the judges that year).

“If you’re on the jury, you can’t propose an artist for the shortlist if they pose a conflict of interest. If such an artist is proposed – i.e. by another juror – then you can’t take part in the decision to carry that artist forward to the shortlist or not,” says a Tate spokesperson.

So where next for the prize? The Art Newspaper writer Louisa Buck, a judge in 2005, says any initiative giving money to artists should not be abolished.

“As state subsidies dwindle, the sad truth is that prizes have erroneously become an alternative revenue stream for artists and institutions,” she says. “Over its lifespan the Turner Prize has certainly been a shapeshifter but it’s no longer centre-stage because contemporary art has now broadened out into the mainstream and no longer needs foregrounding.”

Lisa Le Feuvre, executive director of the Holt/Smithson Foundation and a judge in 2018, says the Turner Prize should continue. “Why? Because it demonstrates to a broad public that art exists in this version of the present and that it is relevant.” On whether the prize has led change or followed it, she says: “I think it is there to observe changes and to invite debate.”

Renton at Goldsmiths concludes: “If we’re now taking the Turner Prize for granted, maybe it’s doing its job? Categorically, it hasn’t run its course.”

Gareth Harris is a freelance arts writer

History

The Turner Prize was first awarded in 1984. It was founded by a group called the Patrons of New Art under the directorship of Alan Bowness, the director of Tate between 1980 and 1988. The group believed that Britain should have an award for visual arts, an equivalent to the Booker Prize.

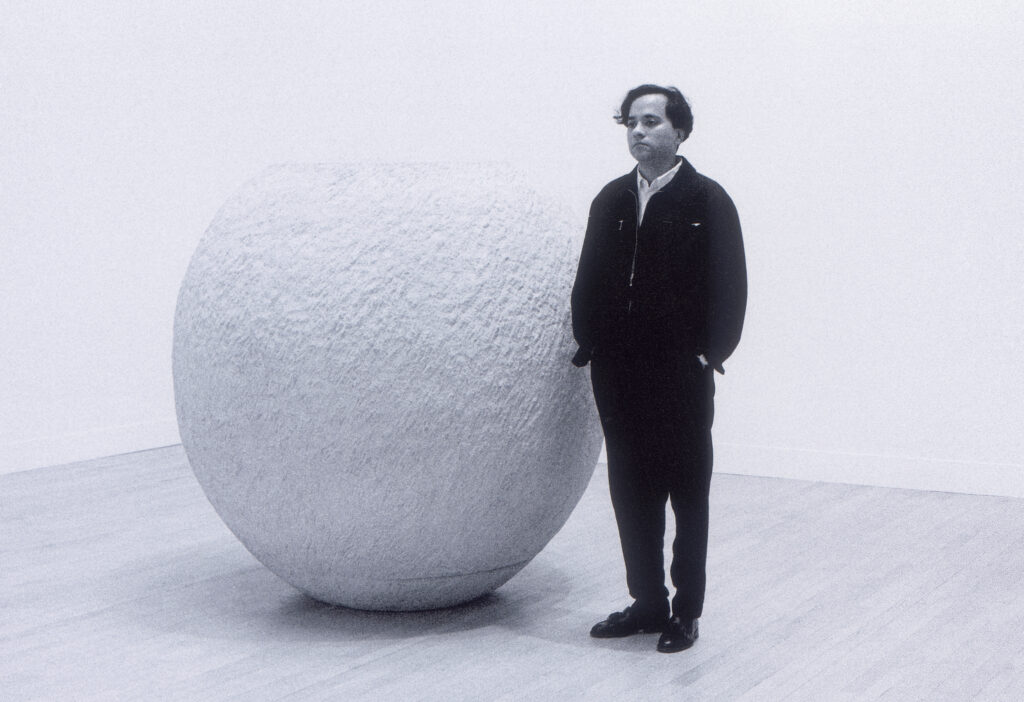

The first winner was Malcolm Morley, who beat off competition from Richard Deacon, Gilbert and George, Howard Hodgkin and Richard Long. Other winners have included Tracey Emin, Anish Kapoor, Damien Hirst, Antony Gormley, Steve McQueen and Grayson Perry.

The prize has twice been won by a collective rather than by individual artists – Assemble won in 2015 for its work on the Granby Four Streets project in Liverpool, and the Belfast-based Array Collective won in 2021 for The Druithaib’s Ball installation. In 2019, the prize was shared by all of the nominees after they wrote a letter asking the judges not to choose one single winner.

Criteria

The Turner Prize is awarded to a British artist. “British” can mean an artist working primarily in Britain, or an artist born in Britain working globally. The prize focuses on their recent developments in British art rather than a lifetime’s achievement. The prize has no age limit, but this wasn’t always the case.

From 1991–2016 the prize had an age limit of 50. This played an important role in introducing the work of emerging artists. The lifting of the age restriction recognises that artists can experience a breakthrough in their work at any age. Harsh headlines “What’s the point of the Turner Prize?” Tom Lubbock, Independent, 2007.

“The only thing more stinky than this ‘art’ is the smug pooh-bahs who gave it a prize” Quentin Letts, Mail Online, 2016 “Thought the Turner Prize couldn’t get any dafter? It just did” Waldemar Januszczak, 2021, writing on his website. “From buzzy to box-ticking: how the Turner Prize lost its way” Alastair Sooke, Telegraph, 2024.

Judges

Tate selects a new panel of judges every year. The panel includes gallery directors, curators, critics and writers. At least one member is from abroad. This balances those who focus on British art or who work in Britain with those who see British art in a broader context.

The members of the Turner Prize 2024 jury were: Rosie Cooper, the director of Wysing Arts Centre; Ekow Eshun, writer, broadcaster and curator; Sam Thorne, director general and CEO at Japan House in London; and Lydia Yee, curator and art historian. The jury is chaired by Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain.

Prize money

The award total is £55,000. The winner gets £25,000 and £10,000 goes to each of the other shortlisted artists. The winner of the UK’s other big artist prize, Artes Mundi, gets £40,000.

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.