Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The Wellcome Collection’s permanent exhibition, Being Human, was said by disability researchers to be the most accessible museum space ever in the UK when it opened in London in 2019.

This enthusiasm partly stemmed from the exhibition’s reconfiguring of tiny but important details such as the placement of benches so that wheelchair users could enjoy the same views of the exhibits as other visitors, and display plinths painted black to boost their visibility. Exits were obvious for those with anxiety who might want to leave.

The gallery’s development involved consultation with a wide range of disability groups. Exhibition design was by Assemble, a multi-disciplinary collective working across architecture, design and art, with graphics from Kellenberger-White and lighting by DHA Designs.

Captions included both braille and written text, and a tactile map and interpretations of key objects were designed and produced by Tactile Studio, a design agency that focuses on creating accessible exhibitions and displays.

“Being Human feels like a very deliberate anchor for the way in which the stories we are telling in our exhibitions are entwined with our determination to make sure those experiences are available to the widest audience,” says the Wellcome Collection's senior curator Emily Sargent.

“But also, we develop content in a way that is properly and thoroughly embedded [with] the people whose experience that represents.”

Despite the progress made by organisations such as the Wellcome Collection, there are still too few museums that take disability seriously and have changed their working practices accordingly.

Being Human

Being Human, a permanent gallery at the Wellcome Collection in London, opened in 2019.

The gallery, which explores what it means to be human in the 21st century, is divided into four sections: Genetics, Minds & Bodies, Infection, and Environmental Breakdown.

The displays were developed with the support and advice of two advisory panels – one was made up of senior scientists, and the other featured artists, activists and consultants.

The latter was organised in collaboration with the University of Leicester’s Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, and focused on the representation of disability and difference.

The gallery was designed by Assemble, a multi-disciplinary and socially-focused collective that works across architecture, design and art.

It is still hugely underrepresented within museums, with institutional approaches to interpreting collections geared to normative ideals of body and mind.

“How can we go beyond minimum compliance to build collective shared ambition to make gold standard access?” asks Richard Sandell, co-director of the University of Leicester’s Research Centre for Museums and Galleries.

“How can we create museums where stories of disability are not a rarity, given that differences are not rare in real life? How do we build that so it happens, not as shining projects, but as a core way of moving forward?”

Historically, museums have approached questions of disability from a perspective biased towards subjectively desirable characteristics.

Stewart Emmens, curator of community health at the Science Museum, whose Wellcome Galleries contain the world’s largest medical collection, believes that historical approaches to collecting material on disability were reductively focused on the objects themselves, rather than the stories associated with them.

“The result is large collections of often very personal items gathered over many decades that are largely lacking individual experiences of use and personal anecdote about their value and meaning,” he says.

He describes how disability was often presented in terms of fixes or limitations, “improving” people’s lives, or exploring “causes”.

“The missing voices of disabled people from previous displays were missed opportunities for greater nuance,” he says.

Emmens highlights the example of a display in the Science Museum’s previous medical galleries that juxtaposed a simple wooden peg-leg with a more complex leg prosthesis.

Science Museum

For the opening of Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries at the Science Museum in 2019, the curatorial team co-created a film, Roads to Recovery, with a group of people recovering from severe brain injuries.

Participants gave objects representing their recovery process to form a small display. “We wanted to ensure our visitors would see people like them reflected in the galleries,” says Natasha McEnroe, keeper of medicine at the museum. “Using art and other creative practices was a particularly effective way to do this.”

For a separate project, When Medicine Defines What’s Normal, artist Siân Davey created a series of 22 photographic life-sized portraits responding to questions around identity – her portrait of Ruth and James, who has sickle cell anaemia, is below.

“Next to the portraits, visitors can listen to the person recounting something about their life – not necessarily about their health condition,” McEnroe says.

Research for the museum’s world war one centenary exhibition, Wounded: Conflict, Casualties and Care, revealed that, for many, comfort and ease of use was more important than ingenuity and expense. But without the voices of the users, stories about objects such as these are lost.

In February 2023, the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) announced the £1m Sensational Museum project, a collaboration between five universities and 11 organisations including the Museums Association, with the aim of reimagining museums’ disability representation.

The core research team will work with “disabled and non-disabled audiences, staff and sector organisations”, according to the AHRC, to test new approaches to areas including access, inclusion, collections, cataloguing and communicating with the public.

Project leader Hannah Thompson, a professor at Royal Holloway, University of London, views the approach of museums to disability as deeply embedded in historical precedent.

“In the 19th century, the big Victorian exhibitions and museums were about putting objects on display for people to come and look at – and that’s basically still what museums do,” she says.

“They have this look-and-learn basis, which kind of defines the museum. And there’s a perception that there’s a very small minority of people who might need some help to access this material.

“So, museums respond to that very small minority by doing a very small number of things. But actually, everyone would benefit from a broader range of ways to access information”.

Jenni Hunt, community engagement officer at the Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret in London has researched the representation of disability within British museums as part of her PhD at the University of Leicester.

She says that a piecemeal approach to collecting and interpreting objects related to disability has affected representation by entrenching stereotypes.

“The kind of stories that were preserved were of people who were exhibiting themselves as oddities, which can be quite stigmatising,” Hunt says. “Or there is this idea of heroism and overcoming disability, or not really considering that someone was disabled.”

This confusion, she argues, persists despite the historical abundance of relevant stories.

In Plain Sight

In Plain Sight, a temporary exhibition that opened at London’s Wellcome Collection in October 2022, invited visitors to encounter different experiences of sighted, partially sighted and blind people to consider the subjectivities of vision and blindness and question the central place sight holds in society.

It brought together 140 objects and artworks and covered four themes: symbolism of the eye; bias in visual perception; eyewear and identity; and the interconnection between senses.

The visual sense has long dominated and conditioned the language, value systems and institutions we have constructed.

In Plain Sight asked: “What happens when we open ourselves up to seeing in different ways?”In Plain Sight, which ran until 12 February, was curated by Wellcome senior curator Laurie Britton Newell and independent curator Ligaya Salazar. Exhibition design was by OMMX, with graphics from Sara de Bondt and Luke Gould.

The current museum landscape reflects this chequered history. According to the latest estimates of the Office for National Statistics’ Family Resources Survey, 22% of the UK population had a disability in 2020/21.

However, not only are museum displays, exhibitions and collections unrepresentative, museums also often regard disability as an “add-on” component as opposed to something that is central to their decision-making.

This comes despite a broader societal and cultural shift over the past 10 years towards lived experience that has platformed the voices of those previously unheard.

The University of Leicester’s pioneering work in this area includes the project Rethinking Disability Representation in Museums and Galleries, which looked at new forms of disability interpretation and representation in the UK, and Everywhere and Nowhere with the National Trust, which considers underrepresented voices around disability across its sites.

For Sandell, institutions need to build on increasing inclusion of previously marginalised voices to sustainably change decision-making processes across all parts of museum activities, and move beyond minimum access requirements.

“We’ve looked around and seen a tendency for museums to delegate, like handing over a space to disabled artists, for example, for a period of time, which seems radical on one level, but also tends to leave the museum quite unchanged,” he says.

Instead, a “process of exchange” could enable the co-production of exhibitions, where learning is traded between organisations and disabled people and negotiated between them.

“The big thing I think we’ve done is to move away from a kind of ‘add and stir’ inclusion approach where you literally take what you’re already doing, and add in disabled people or disability,” Sandell says.

“Museums can be much more active, socially purposeful, in that inclusion of disabled stories in events and experiences”.

So how can this momentum continue? Esther Fox is head of the Accentuate programme at Screen South, which creates opportunities for D/deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people to participate and lead in the cultural sector.

She oversees Curating for Change, working with 20 museums across England to deliver a programme for disabled people who want to pursue a career in museums.

She also led History of Place, a project that explored 800 years of D/deaf and disability history in locations, such as the Royal School for Deaf Children in Margate.

“When I was working on History of Place with volunteers across the country it became clear that I was the only disabled person in the curatorial cohort pulling those exhibitions together,” she says.

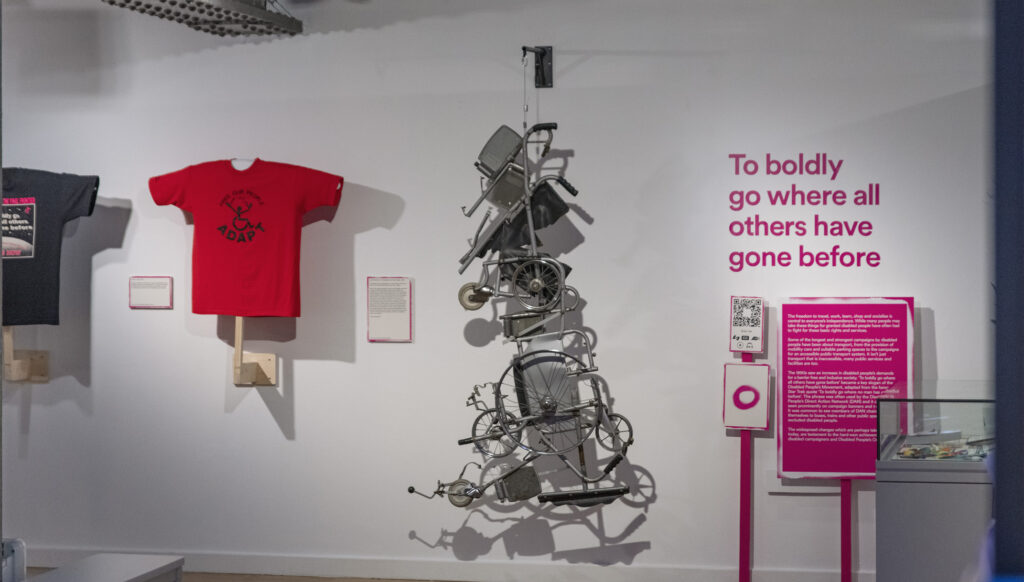

Nothing About Us Without Us

This exhibition (until 16 October) at the People’s History Museum in Manchester explores the history of disabled people’s activism and ongoing fight for rights and inclusion.

The museum says it is the most accessible exhibition it has ever held. Those visiting in person can access British Sign Language (BSL) interpreted, audio-narrated and captioned films, along with audio format information via QR code in the exhibition gallery.

Printed copies of Large Print and Easy Read guides are available, as well as braille transcriptions of the exhibition content. Magnifying glasses, colour overlays, ear defenders and sensory bags are also on offer.

The exhibition website features BSL interpreted, audio narrated and captioned films, audio format information, Large Print and Easy Read guides and a visual story for the exhibition.

“And I was getting the text and thinking, ‘oh god, I wouldn’t say it like that,’ or, ‘why have you picked out that point?’ and it made it clear to me that if you don’t have D/deaf, disabled or neurodivergent curators, you’re going to have that issue because other people aren’t going to come to it from that lived experience perspective.”

Fox highlights the importance of tackling recruitment practices and unconscious bias and collecting beyond tokenistic inclusion.

“Disabled people have complex and multifaceted identities that move across different types of experience – that is what I am interested in,” she says. “Most of these sort of exhibitions are about a disability rights kind of struggle. When can we move onto a more nuanced approach?”

Thompson says one of the aims of the Sensational Museum is to tackle the organisational structure of museums.

“What we’ve already found is that there’s some good stuff happening in terms of access and inclusion across the UK,” she says.

“But it is little pockets of excellence that happen almost despite the structure of the museum. It’s almost always individuals who care really deeply about this and make things happen, but often they’re fighting to get this done and there’s no budget and no time.”

The broader question, as ever, relates to top-level museum policy – alongside funding.

While progress through accessibility and broadening narratives has been partially effective, those in the field think museums should continue to prioritise inclusivity, actively engage with disabled communities, and challenge existing norms to create genuinely representative spaces for all.

Rob Sharp is a freelance journalist.

Esther Fox, Richard Sandell and Hannah Thompson are speaking at this year’s Museums Association Conference in Newcastle-Gateshead (7-9 November)

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

You must be signed in to post a comment.

These pieces are still suffering from the same old misconception. I can see plenty of references to inclusivity and anti ableism being rooted in the visitor experience. Disability inclusivity requires a wholesale overhaul of museum policies wrt employment. There are museums in UK lauded for being inclusive that have no disability access to working areas. While it may not be possible to alter the fabric of a listed building these institutions should not be held up and praised for their inclusivity. Similarly there needs to be a recognition of the value of volunteering, internships and training posts to disabled people in terms of our entry into Heritage Sector employment. My experiences are limited to Wales so this may not be true everywhere but too often disabled people are having to compete against able bodied people for these entry posts even if they are especially beneficial for disabled people. The rational seems to be to spread the opportunities around. The problem is that when one gets feedback from Heritage Sector employers they highlight these schemes as places where disabled people can gain the necessary experience and these are often the only opportunities for disabled people to gain this experience. End result is a sector that is adding to its exclusion of disabled people ironically claiming that it is doing so in the interests of fairness.

This is a really good point. As a neurodiverse curator, I can see that many museums are trying to produce more inclusive, accessible exhibitions and public programming but are not successfully replicating this behind the scenes. I don’t think this is deliberate, I suspect it is more due to a distinct lack of understanding of the varying and often contradictory needs of people who face access challenges and of course the eternal funding issues. What I think we need as a sector is to better understand the perspectives of people who face access challenges so that better practice can be embedded without those of us who do have these challenges having to regularly advocate for it. Advocating for access is exhausting!