Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The Horniman Museum and Gardens in south London boasts one of the most comprehensive collections of musical instruments in the UK, holding almost 10,000 objects made to produce sound from across the world – from ancient Egyptian bone clappers in the shape of human hands, to electric guitars and synthesisers.

The venue’s Music Gallery exhibits more than 1,300 of these items, including a strikingly dense wall display. But having such an awe-inspiring collection brings its challenges, says Mimi Waitzman, the Horniman’s senior curator of musical collections and cultures: “People regularly ask: ‘Well, why can’t I play them?’.”

Lamenting the apparent inconsistency of this attitude, Waitzman says: “They don’t think that about a chair, or a pool table, or a tea set, or cutlery or any of the other objects that we see in museums. Maybe people just have a bigger emotional connection to music and musical instruments.”

Negotiating the tension between music’s emotional immediacy and the traditionally contemplative exhibition space is a challenge for any museum creating displays about the artform.

But as Waitzman argues – and many museums are showing – the strong connection that people feel with music is an asset that institutions can tap into to help audiences explore their natural musicality.

The Horniman uses a variety of techniques to break down perceived barriers to engaging with its musical collection and bring its objects to life. Listening tables allow people to play recordings of the instruments on display and hear additional commentary on them. And there is a hands-on space where visitors can try out replica objects. The museum also programmes regular informal live performances in its spaces.

Waitzman says: “From a harpsichord to steelpans and everything in between, these are much more approachable than formal concerts.” Visitors can come and go as they wish and chat with performers. “We’re trying to say: ‘Whatever music it is, interact with it.’ Don’t let anything get in your way.”

The Horniman gallery suggests different ways of exploring music – through films highlighting its cultural contexts and uses, for instance, and displays focusing on how instruments are made or function.

“There are lots of doors into the collection, depending on the way people’s minds work and how they perceive things,” Waitzman says. “But every door in is a good door in.”

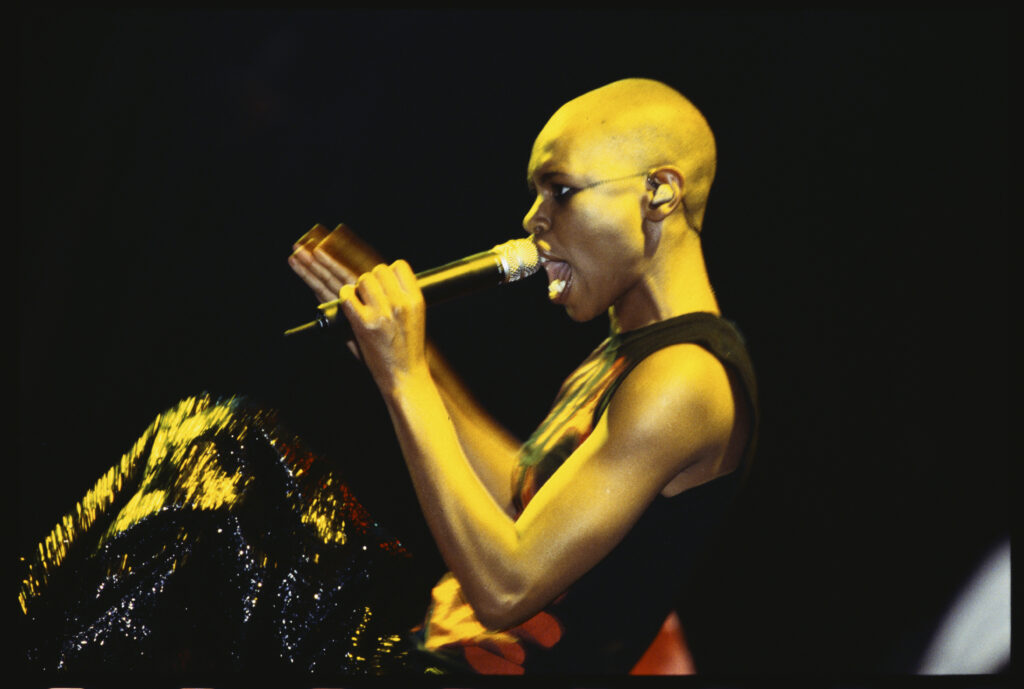

The experience of music is not purely auditory: other sensory aspects are often key elements. Museum galleries are well suited to exploring the visual dimensions, such as the outfits worn by performers. The Victoria and Albert Museum’s David Bowie Is exhibition in 2013 featured more than 60 of his stage costumes.

This year, the museum held a Taylor Swift-themed trail, focusing on 13 stages in the singer’s career, including displays of the pop star’s costumes and instruments. And next year, V&A East’s inaugural exhibition is The Music Is Black: A British Story.

Similarly, for an exhibition celebrating the 60th anniversary of the 1964 film, A Hard Day’s Night, The Beatles Story museum in Liverpool recreated a set of silver-grey suits, which the Beatles wore in the film’s final scene, using the original patterns and fabric from the same supplier. Gordon Millings – the son of the suits’ designer, Dougie Millings – says the project provides a bridge between past and present.

Mary Chadwick, the general manager of The Beatles Story, says this accuracy helps engage audiences with the group’s history: the use of actual measurements highlights how Ringo was the smallest, for example.

The 60 Years of a Hard Day’s Night exhibition sought to replicate sets from the film, including London’s Marylebone Station and a train carriage. The team focused on details such as getting the colour for the train right (despite the film being in black and white) and using engine smells to provide an authentic experience.

This aligns with the wider approach of The Beatles Story, which recreates locations with important links to the group, such as the Cavern Club in Liverpool and the German city of Hamburg.

“We try to really immerse you, taking you back to the 1960s,” says Chadwick. The final room at the venue replicates John Lennon’s White Room from his home in Berkshire, including the musician’s glasses.

“A lot of people do get emotional at the end, as it’s all about peace and love and being kind,” says Chadwick, who adds that it was “lovely” to see people who met at the Cavern Club visit The Beatles Story for an anniversary, and dance in the venue’s own Cavern.

New technologies are creating further possibilities for immersion, as a recent show at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery demonstrates.

This summer the museum hosted In Pursuit of Repetitive Beats, a VR experience by East City Films that explores the early days of acid house. It travels to Nov Brighton Dome (5-24 Nov) next, then Belfast XR Festival (22 Feb-25 Mar).

The production was premiered as part of Coventry’s City of Culture 2021 programme and has since featured at Melbourne International Film Festival.

The 45-minute VR experience recreates an illegal Midlands rave set in 1989, incorporating oral histories from people involved with the events. Scenes include a police station, a car on a motorway and the warehouse party itself, complete with other dancers and trippy lighting effects.

Anthony Crutch, brand and marketing manager at Birmingham Museums Trust, says: “That’s the bit where people who are really into it let go. You can see them dancing along, totally immersed in the experience.”

He says reactions afterwards have ranged from euphoria to emotional exhaustion. The Birmingham show also included a display of flyers – which for some people prompted memories of DJs and long-lost venues – and a replica phone box, where visitors could record their own oral histories.

The impact was felt beyond generations who had actually experienced this history, with Crutch saying that even people who hadn’t lived through the scene had been emotional when leaving the show.

The Reverb exhibition (until 10 November) at 180 Studios in London, which showcased works collected by the Vinyl Factory music company over the past 20 years, has similarly challenged audiences to stretch their musical horizons – historically and aesthetically.

Sean Bidder, the venue’s curator and creative lead, says one of the most popular works in the show was a room created by Turner Prize-winning British artist Jeremy Deller, featuring a video documentary about the UK’s rave era.

“The film feels vital musically, in that much of the electronic dance music created in the late 1980s is still hugely influential today,” says Bidder. “But generally, young audiences are also fascinated to see the cultural upheaval the music engendered, perhaps because it’s difficult to imagine any such thing taking place in Britain today.”

Bidder says the exhibition’s varied works synergise visual art and music. He believes this approach can create a multi-directional sensory experience that immerses the viewer into an alternative space removed from their everyday reality.

Italian musician Caterina Barbieri, for example, partnered with visual artist Ruben Spini to create Vigil 2.0, which combines a tranquil electronic score with a video of the sunrise and sunset. This was viewed from behind a large melting ice block, with images from the screen reflected in the pool of water below. “It’s transportative,” says Bidder.

The varied ways in which people respond to music were also explored in the Turn it Up exhibition, which ran at Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum before moving to the London outpost for a second stint that ended this year. The show had a strong emphasis on personal stories, says Stephen Leech, the exhibition’s lead curator.

Irish painter Jack Coulter, for instance, has synaesthesia, a condition that creates sensory crossovers, which means he can see sound as colours and shapes, as well as hearing it.

The museum displayed a painting by Coulter alongside music he listened to, and his words, to demonstrate the sensory and emotional connections he made. Other stories included those of the Deaf dancer Chris Fonseca, and Laurie Horam, who became a busker at the age of 79 after previously considering himself unmusical.

Leech says the museum’s initial research found that most people don’t see themselves as musical, so showcasing such narratives helped the exhibition emphasise the artform’s universality and accessibility. This goal was also achieved through playful installations where people could create music with no formal experience.

A highlight for many was a “musical playground” – an interactive light and sound installation by Australian artist group Amigo & Amigo. Creating different sounds through the placement of Lego Duplo bricks was likewise a hit with young families.

The exhibition featured unconventional yet accessible instruments, says Leech, such as a pyrophone – a flame-powered organ from the 19th century – and a glass harmonica played by spinning a wheel, as well as instruments made from reclaimed junk and everyday items.

In addition, the exhibition encompassed the science of how music impacts behaviour – exploring this through everyday scenarios such as a gym, a bedroom and an office. An interactive display focusing on how driving ability is affected by sound was particularly popular.

The Science Museum exhibition signals the range of ways to address musical themes. But perhaps the ultimate mark of success is the ability to ignite people’s own instinct to participate.

Evaluation of Turn it Up’s Manchester stint meant that when it moved to London, more hands-on opportunities to play instruments such as mini-synthesisers and steelpans were included.

“As ever, people wanted more opportunities to make music,” says Leech.

Jonathan Knott is a freelance journalist

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.