Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The first time I visited Beyond the Bassline at the British Library (28 June-19 July, 2024), I could feel that this exhibition was doing something special.

This was a serious exhibition, afforded the respect that the London venue would give any of its blockbusters. Items of historic significance were placed behind glass in display cases, labels were thoughtful and informative, the exhibition design was to a high standard.

Yet, here in this library, the security guard was bopping his head to music coming from a set of headphones. Unlike the usually silent procession around exhibitions at national museums, visitors were really moving. They were feeling the exhibition, not just studying it. Strangers were striking up conversations; reminiscing, critiquing, praising. It felt alive. It felt joyful.

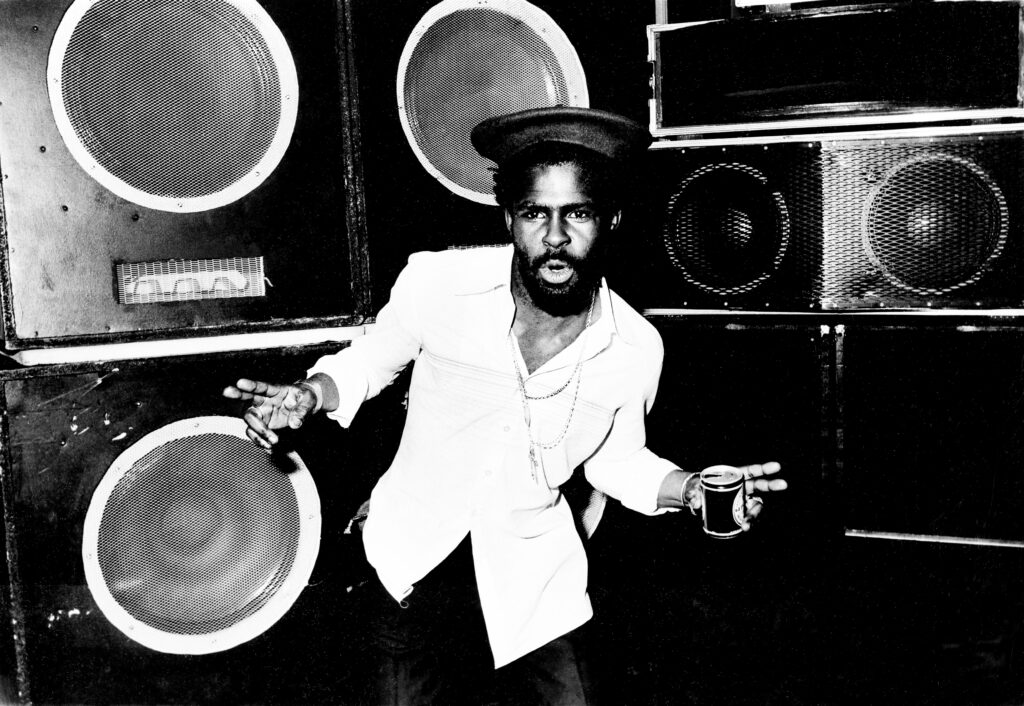

And this was a moment worthy of joy, a place where original dub protagonist King Tubby’s bass bin, a set of dice from the Manchester’s Reno Club, the camera recorder that music entrepreneur and DJ Jamal Edwards used to start SB.TV – which played a role in launching the careers of British rap stars Stormzy and Dave – could be, and were, all displayed.

A place where music legends John Blanke, Shirley Bassey, Lord Kitchener and Little Simz are acknowledged as playing their part in the history of Black British music.

And I acknowledge that the very existence of this exhibition at the British Library would have brought joy to many people, when the art of Black people in Britain has so often been ignored or commodified by mainstream institutions. I understand the significance of this national acknowledgment.

But I didn’t personally care much for where this exhibition was held. Black music has survived and thrived despite – indeed, to an extent, because of – being neglected, forced to innovate underground with bits of scrap metal to make instruments and old-school Nokia mobile phones to make beats.

For me, the joy was in the narrative that curator Aleema Gray and Mykaell Riley, the director of the Black Music Research Unit and a former member of reggae band Steel Pulse, and their team of collaborators had created. This is because it’s not a narrative of pure, uncomplicated joy – it’s much better than that.

The first “site” visitors were immersed in was “The Ocean” – specifically, the Atlantic Ocean. The first sounds you heard were waves, followed by Yeye Ba ’Beji Ro (Song For Oshun, a Yoruba deity associated with water), while immersed in blue curtains.

It conveyed a subtle message that the Atlantic is a sacred site. A place where millions of African people were trafficked and died through enslavement. A site of rupture, where a diaspora was created by force. But the people who made it across the Atlantic took with them a beat. One they passed down the generations. A beat still heard at the heart of so many genres of music.

This is a theme that continued throughout an exhibition that showed how music has always been part of the “frontline” of the struggle for freedom – and that remains the case. The exhibition declared: “In the face of racial tensions and exclusionary immigration bills, music becomes our frontline.”

On display was the Ku Klux Klan hood a member of Steel Pulse wore to perform a song featuring the lyrics “stand strong Black skin”. A display case containing poet and musician Benjamin Zephaniah’s vinyl sleeve for Rasta is displayed alongside a banner for the Brixton Defence Campaign, which arose from the Brixton uprising of 1981.

Many of the clubs that the exhibition delved into were created because Black people couldn’t go anywhere else to dance away the stresses of living in a racist society. A collaboration with Roundhouse Young Film-makers resulted in the creation of the artwork, Self-Made, which beautifully explored the DIY ethos of Black British music.

An ethos created out of necessity, because there was no help coming from anywhere except from within the innovation of our own communities.

This isn’t joy handed to us on a plate. It’s hard earned, fought for, skilfully crafted over generations. People have survived enslavement, segregation and hostile environments to create sounds that bring pleasure and connection to so many.

It’s part of the survival that Guyanese historian Walter Rodney spoke of in his book Groundings with My Brothers: “Apart from the measurable negative effects, one must also consider that a fantastic amount of physical and social energy went into the defensive task of sheer survival. We did survive not only in Africa, but on this side of the Atlantic – the greatest miracle of all time. And every day, Black people in the Americas perform the miracle anew.”

That survival has resulted in the creation of steelpan, sound systems and art that was on display. It has led to blues, gospel, soul, reggae, hip-hop, garage, grime, drill and more – music that has sustained life and brought happiness to so many in a world that can be oppressive.

I must show caution here. Sometimes, people can make it seem as though the death and enslavement of millions of people was worth it because we got some nice music out of it. This isn’t what I’m saying and it’s not the exhibition’s message.

The message I took away from Beyond the Bassline is best captured by the astonishing artwork, Iwoyi: Within the Echo, which explored the radical potential of Black British music to manifest reparative futures. For most people, it would have been the last artwork they engaged with – and it represented a powerful conclusion.

People were sat around the edges and laying on cushions on the floor, immersed in the five-channel film and sound installation that weaves original film and archival footage. At one point, the narrator advised the listener in patois: “Listen chargie, man haffi practice building life.”

In a world where we still face so many struggles, that remains the root of our survival. We must practise building life and making freedom – and that will continue to happen to a beat.

Miles Greenwood is the lead curator of transatlantic slavery and legacies at National Museums Liverpool. He chaired a session at the Museums Association Conference in Leeds on Beyond the Bassline

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.