Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

Everyone has their own experience of the medical world and the pandemic has given that a sharper edge. Medical museums, collections and exhibitions have never been more relevant and relatable.

“They document some of our most intimate and significant life experiences and help us make sense of the hopes and fears and pain and pleasure associated with our health,” says Katie Dabin, lead curator of the Cancer Revolution: Science, Innovation and Hope exhibition, created by the Science Museum Group (SMG).

“Crucially, they act as spaces to open up conversations and explore changing attitudes about our relationship to medicine and health and control of our bodies.”

Museums can inspire debate and engagement where medical science and society intersect. They are ideally placed to explore past legacies and contemporary issues, such as the ethics of gene editing, and can contextualise hot-button issues in the historic struggle to combat disease, leading to a more nuanced understanding.

London’s Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret is bringing its 200 years of history to life with a £125,000 National Lottery Heritage Fund grant. This year is the operating theatre’s bicentenary and the museum’s 60th anniversary. From 1822 to 1862, surgeons operated on women there without anaesthetic or antiseptic.

The theatre is in the roof space of St Thomas’ Church, which was originally used by St Thomas’ Hospital apothecaries. “We’re telling the stories of female patients, surgeons, medical students, ward sisters, nurses and porters,” says Sarah Corn, the director at the Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

Visitors who climb the spiral staircase to the theatre may wonder how patients made it there. So the museum has recreated the doorway that led to the adjoining women’s ward. The museum is also working with Kingston University students on a film that will be projected onto the door, showing what lay beyond. Ghostly figures will bring female patients towards the theatre as visitors imagine the unfolding horrors.

The museum created an augmented reality experience with tech specialist Arcade when the pandemic curtailed its weekend talks. The free app brings people face-to-face with 19th-century surgeon Benjamin Travers on their mobile devices. Now lockdown has ended and the museum has reopened, visitors can once again experience compelling in-person activities such as a talk about Victorian surgery or volunteers demonstrating pill-making.

Corn hopes the museum can empower individuals and local groups. A community engagement officer (funded through the Heritage Fund grant) will build relationships with local groups, as Corn says it is really important for the museum to work collaboratively. Its events programme is a platform to bring in people’s lived experiences and raise awareness around women’s health.

“We try to tell stories accurately and sensitively, bringing in experts and having open conversations,” says Corn. “We must not forget what happened in the past or the journey that we’ve all been on to get here.”

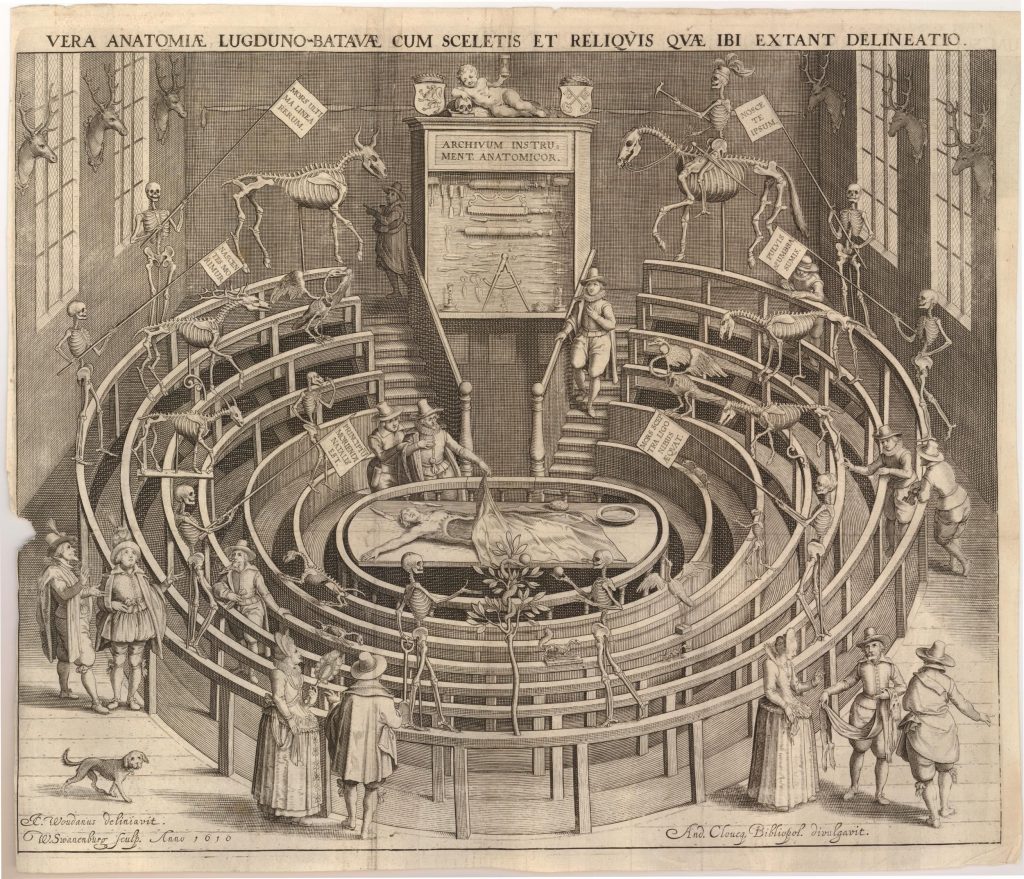

National Museums Scotland (NMS) traces the connective tissue between past and present in its Anatomy: A Matter of Death and Life exhibition, which opens on 2 July. Spanning 500 years, it highlights Edinburgh’s role in medical study and teaching. It opens with sketches by Leonardo da Vinci from the Royal Collection. It also reveals the circumstances behind the Burke and Hare murders in the early 19th century and shows how tightly regulated anatomical dissection is today.

“The exhibition balances the beauty of anatomy with the darker stories that have come from its study. We’ve showcased both aspects with the utmost sensitivity and respect,” says Sophie Goggins, senior curator, biomedical science, at NMS.

Artefacts include an anatomical sketch of a centenarian by Da Vinci who he had met. “It’s one of the first objects in the exhibition and sets the tone,” says Goggins. “It’s important we give space and identity to the people who have been dissected.”

The exhibition recognises the contribution of body donors, or “silent teachers” as they are known. NMS has worked with Scotland’s five body donation centres. “We’re honoured that the University of Edinburgh is letting us display its beautiful book of remembrance, which contains the names of everyone who has chosen to donate their body,” says Goggins, who has built relationships with universities and research centres to keep the medical collection current.

NMS is mindful of the exhibition’s emotional impact. “There will be representations of skeletons and dissections, but we only have one example of human remains and that’s a purposeful choice,” says Goggins. “We have worked closely with our visitor experience team to enable them to deal with questions people might have before they enter. It is an upsetting subject, so we want everyone to be as comfortable as possible.”

Dabin at the SMG believes that museums should never “underestimate our audience’s willingness to engage with tough, complex and emotive issues”. Nevertheless, the organisation, which developed the Cancer Revolution: Science, Innovation and Hope exhibition with Cancer Research UK, faced the question: “Can we make an exhibition about cancer that visitors choose to come to?”

“With one in two of us being diagnosed with cancer in our lifetime, it felt like an urgent topic to tackle,” says senior exhibitions manager Jane Brown. “Audience research showed that fear of cancer was really high but that knowledge was really low, so we wanted to make sure that visitors could easily access answers to their questions. We also wanted them to feel more hopeful about the outlook for living with the disease.”

The exhibition team ensured that science and patient stories had equal status. To address a lack of material culture and stories about cancer, the SMG developed the Living With Cancer collecting project.

A call-out to online patient networks through Cancer Research UK for objects, images and stories produced amazing responses, says Dabin. At the end of the exhibition, a book about the collecting project shares images and stories of all who contributed.

Consultations with Cancer Research UK’s patient insight panel proved helpful. They showed that the exhibition needed to work for families and schools.

“The consultations also gave rise to exhibits, including a soundscape recorded at the Tameside Chemotherapy Day Unit in Manchester,” says Dabin. A Wall of Hope lets visitors share stories, memories of loved ones and advice. The team also worked with the National Cancer Research Institute on a voting station for visitors to indicate which research areas to prioritise. The results will feed into future scientific conversations about cancer.

Developing the exhibition in a pandemic threw up many challenges. “It was the first one I’ve worked on where the designers never saw any of the objects in person until they were installed,” says Dabin.

The team had to weave in stories showing the immense impact of Covid-19 on the cancer community. “We also had to rethink interpretation and its delivery on gallery, using fewer touchable elements and replacing headphones with sound cones.”

After launching at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester, the exhibition will move to London’s Science Museum (25 May 2022 to January 2023).

“Medical museums have a direct impact on people’s sense of agency,” says Nat Edwards, the chief executive of the Thackray Museum of Medicine in Leeds. By helping visitors see themselves in the story of medicine, they can start to shape it.

“Research shows that people get involved in medical careers through significant others in their social circle, often parents, relatives, neighbours or teachers – you need a stepping stone into that world,” says Edwards. “If you come from a community where that’s less accessible, then the museum can serve as a surrogate.”

Co-creation is central to the Thackray Museum’s strategy. A co-producer works with community engagement groups, including the Black Health Initiative in Leeds, to highlight diverse stories such as that of the Windrush nurses.

Having multiple viewpoints creates a rich story that captures people’s imaginations and allows the museum to flesh out difficult issues, says Edwards. The Normal + Me gallery, for example, punctures the idea that there is only one “normal”, healthy body type. Through challenging objects and real-life experiences, Normal + Me proves that there are over seven billion different normals, says Edwards.

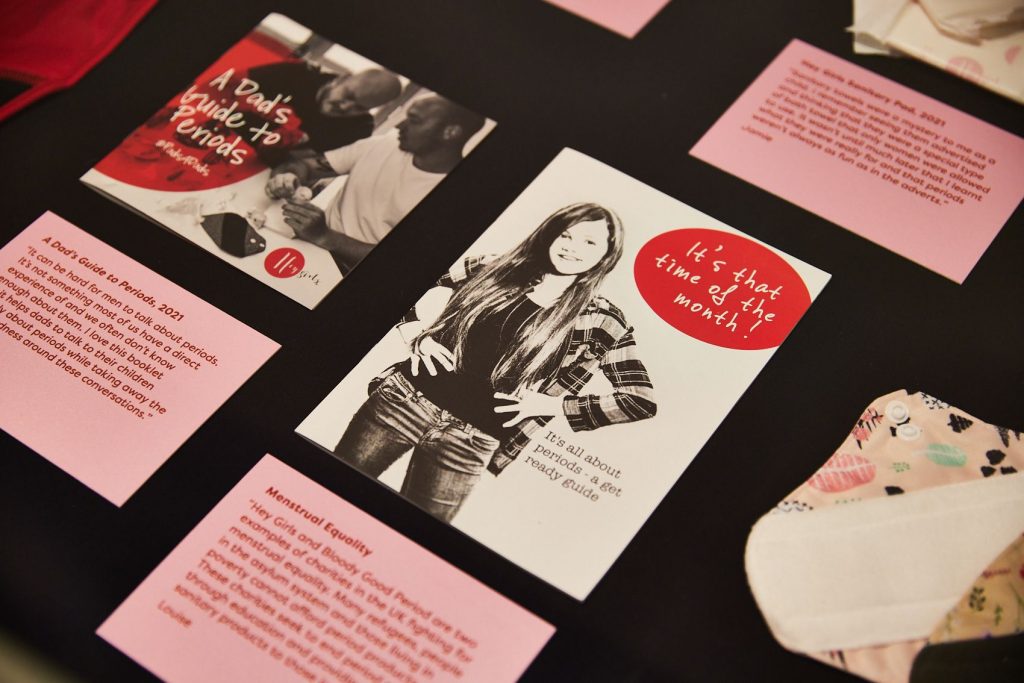

The Thackray’s latest exhibition is Periods – A Brief Jaunt Up North. The museum has expanded the Vagina Museum’s original exhibition with the help of local artists, community groups and Leeds-based period poverty charity Freedom4Girls. Objects in the taboo-busting exhibition include menstruation underwear for trans men, for example.

“The exhibition opens up a dialogue with the visitor about what they wish they knew, what they would tell their past and future selves about menstruation, and what they wish they could share,” says Edwards. It was created with younger, experience-seeking audiences in mind, but Edwards has been pleasantly surprised by the exhibition’s success with families.

“Some people have accused us of being too woke,” says Edwards. “But our mission is to help people discover their own agency and make their own minds up. If we keep that at the heart of everything we do, we tend to make the right decisions.”

Recently, the museum faced criticism for stocking a book about periods by a feminist author, who some see as gender critical.

“If our mission is to help people make their own minds up, then taking the book off the shelf isn’t the right thing to do,” says Edwards. Instead, the museum presents books by trans-inclusive writers and feminist writers. It also runs activities such as Loaded Fries (lunchtime talks on loaded topics). Edwards says the museum has trained staff to be as inclusive as possible.

Museums may be taking a pluralistic approach, but Edwards says there are times “to present something as an absolute scientific fact”. The Thackray was the first museum to become a Covid vaccination centre and is “100% pro-vaccination”.

Edwards also says that contemporary collecting (see p21) is increasingly challenging, with museums grappling to acquire software and gene-editing tools. “Some of the most important medical innovations are iPhone apps that allow doctors to navigate medical processes remotely,” he says.

Despite the UK’s contribution to medicine through the ages, it lacks a national museum of medicine. During the pandemic, medical museums supported each other through the UK Medical Collections Group and webinars such as the Medicine, Myth and Memory: Trusted Voices in the Pandemic conference.

Edwards wants that momentum to continue and believes that with strategic investment there is “a great opportunity to think of that whole network of medical museums around the country almost as a distributed national collection”. The result could be a group of equitable museums that are rooted in diverse communities and are inclusive, story-driven and accessible.

Juliana Gilling is a freelance journalist

Natasha McEnroe reflects on the issues of what to acquire and how

The realisation that we are living through a significant time in the history of medicine could provoke wonder or gloom – but for medical curators, it inspires a sense of deep responsibility as we know the considerable gaps in museum collections over past pandemics and epidemics.

Science Museum medical curators began to collect for Covid-19 in February 2020 and this collecting soon spread across the other museums in the Science Museum Group, becoming both the largest collecting project the organisation has ever undertaken and the one set

in the most challenging circumstances.Difficulties in continuing museum work in lockdown are well documented, but the challenges around collecting Covid-19 related items have been particularly acute. We faced practical issues such as being unable to carry out site visits or spending time with medical practitioners and researchers – often a crucial part of our work. We also addressed ethical issues – should PPE be collected at a time of national shortages, for example?

We found that speaking to personal contacts was essential to our collecting, with pleas for friends and family to save disposable and ephemeral objects. In terms of the early planning of this complex project, I would do things differently now if I had the time again. In hindsight I would have ensured that parameters were stricter and narrower.

In some ways, collecting Covid-19 objects is a task that medical curators have been training for all their professional lives. But the very knowledge of the historic collection held by the team complicated this unique form of contemporary collecting.

How often have we wondered about the decisions made by our curatorial predecessors – was it now going to be our turn for future generations to curse us for missing some vital element of this pandemic that we could easily have acquired had we realised its significance at the time?

Collecting during the pandemic itself has an emotional impact on all that undertake this work. Curators have their work constantly overlapping with their own personal experience of living through a pandemic. The collective and personal aspects of this time are represented by our recent acquisition of a sculpture by artist Grayson Perry that captures the isolating experience of lockdown, featuring a tableau of characters, from his alter ego Alan Measles to chief medical officer Chris Whitty in a dark vision of modern Britain.

The way we collect has also changed due to Covid-19, with the shift to working from home offering the advantage of allowing collaboration with other museums in a more organic way. For example, as the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester acquired a bed and life-support equipment from the NHS Nightingale Northwest, the Science Museum acquired extensive archival material from NHS Nightingale London – enabling complementary collecting that avoids duplication.

As the Science Museum begins to complete its Covid-19 collecting project, we can see that the work we’ve undertaken is crucial. Visitors engaging with the Covid-19 objects already on display in the Science Museum show us that our need for understanding and to see our experiences shared is what makes us human.

Natasha McEnroe is the keeper of medicine at the Science Museum, London

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.