Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The British Museum touring exhibition, For the curious and interested, explores how the foundational collections of the British Museum came together and examines the complex legacy of the naturalist Hans Sloane, who amassed the collections partly with the profits of transatlantic enslavement.

As part of the project, each host venue was tasked with co-curating the displays in collaboration with local communities in order to bring a unique perspective to the exhibition.

To prepare for its time as host, Ceredigion Museum in Aberystwyth, Wales, invited people from the global majority to be part of a co-curation group, Voices from the Edge, whose members helped to plan out how the exhibition should look, as well as contributing their own creative responses.

Following the close of the exhibition earlier this month, Ceredigion Museum’s curator Carrie Canham spoke to Museums Journal to share her reflections on the project and how the museum will build on this work going forward.

Sir Hans Sloane bestowed his vast collection to the nation on his death in 1753, intending for it to be preserved and used for ‘satisfying the desire of the curious.’ His collections became the foundation not only of the British Museum, but the Natural History Museum and the British Library as well.

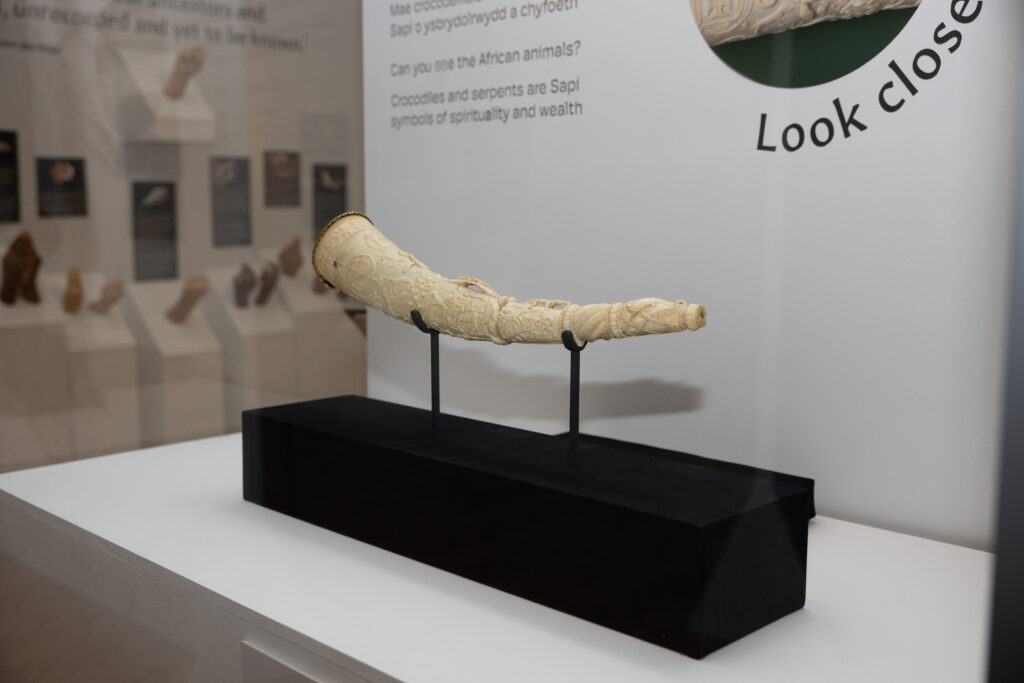

Starting near Sloane’s birthplace at Down County Museum in Northern Ireland, the British Museum touring exhibition, For the curious and interested, reunites a selection of objects from the collection he assembled, including books and prints, cultural objects, and natural history rarities.

Taking a co-created approach, local communities have explored Sloane’s legacy. It was supported by Sloane Lab: Looking back to build future shared collections, which is a Towards a National Collection project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Confronting the complex history behind this collection, which was financed in part by profits from transatlantic enslavement, the exhibition explores the historical purposes of collecting in connection to local and global histories, including those related to enslavement, empire, and colonialism.

We applied to be a partner for this touring exhibition because it was a wonderful opportunity to work with the British Museum, and the project encouraged and provided some funding for a co-created approach from the outset. We saw an opportunity to build relationships with those from the global majority and contribute towards the aims of the Welsh Government’s Anti-Racist Wales Action Plan.

To do this effectively, we approached a member of the Llwy Gariad collective of global majority creative practitioners, Rose Thorn, to co-write an application to the Association of Independent Museums’ (AIM) Re:Collections funding programme.

With additional funding from AIM, we were able to create the Voices from the Edge group. We put out an open call via social media and approached Aberystwyth University’s Student Union to distribute the invitation to people of the global majority, inviting them to find out more about the project.

Everyone who wanted to take part was welcomed, and the group was made up of seven people of different ages, abilities and backgrounds including two students, a full-time mother and a teacher.

They each received an attendance fee for in-person and online meetings plus travel costs. It was also made clear to the group members that they had no obligation to produce work for the exhibition, they could just come and enjoy the meetings if they didn’t have the emotional or time capacity to contribute more.

At the beginning of the project, five members of the group travelled to London to visit the British Museum, British Library and Natural History Museum to see the objects that would be featured in the exhibition and talk to curators and subject specialists about them. This trip was supported by additional funding from the Sloane Lab project.

The group then met on a monthly basis to share their experiences and ideas for responding to the collections amassed by Sloane. They decided early on in the project that they wanted to respond creatively and make new work for the exhibition, both individually and collectively.

They were supported by Wales-based professional creative practitioners in filmmaking, conceptual art and paper-making to produce the art works featured in the exhibition.

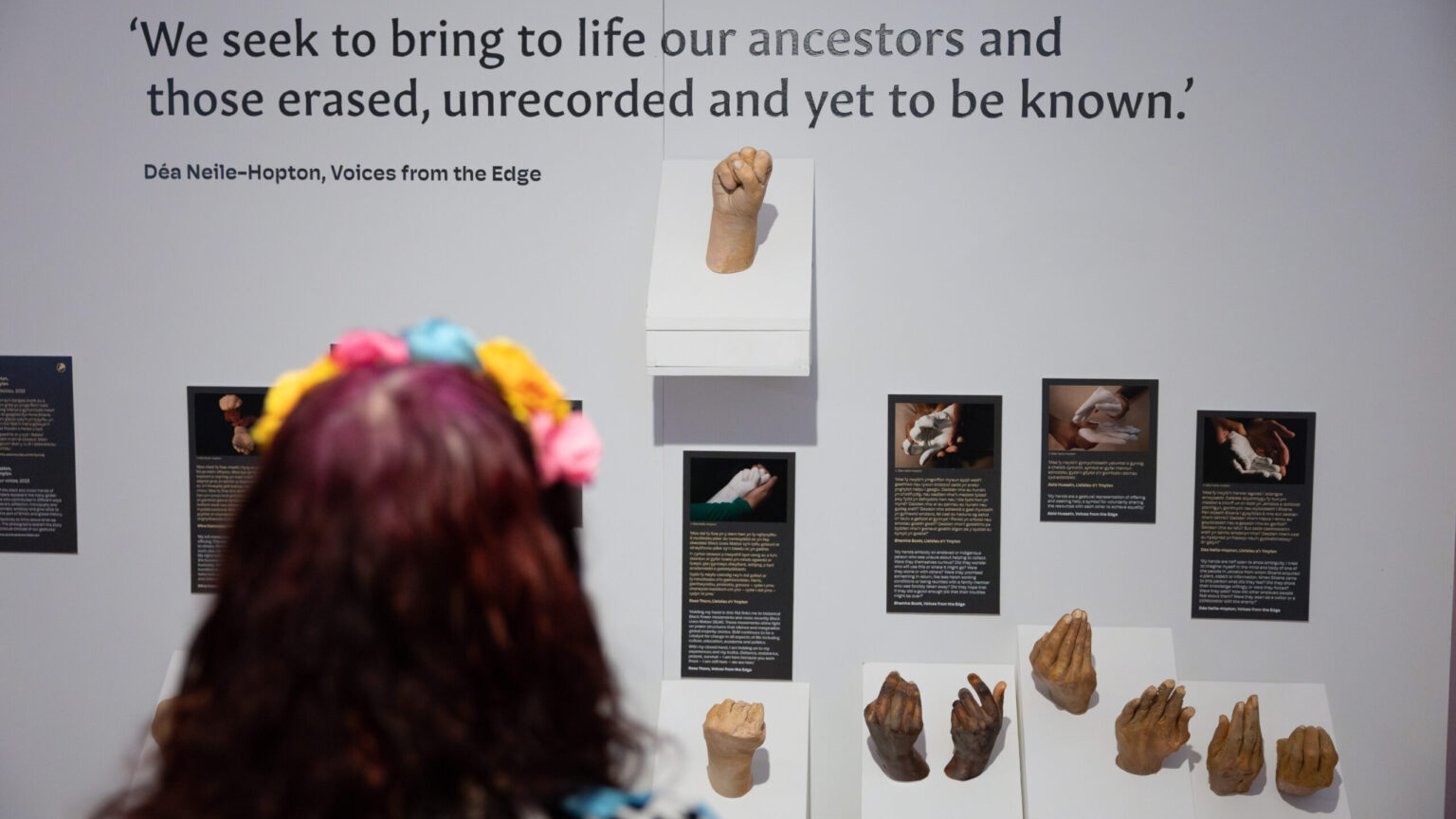

With responses including film, poetry, drawing and sculpture, the group examined the legacy of Hans Sloane through their own lived experiences and identities. The group also influenced the overall design and flow of the space, with 60% of the gallery given to their creative responses.

The exhibition layout was designed around the requirements of two artworks by participants, a large projected film and an interactive 'curtain' textile that visitors were invited to pull back so they could look out to sea. The group contributed to interpretation throughout the exhibition, including panels and object labels for their works and the museum objects.

Excerpts from poems produced by Shamira Scott and Déa Neile-Hopton were also enlarged in graphic text at key points in the exhibition. The group’s voices and their conversations drive the exhibition.

One of the major learning points for us was around colonisation and how this history continues to affect people of the global majority today.

When looking at topics such as colonialism and enslavement with a global majority group, there is a need to create a culture of care, which as a former therapist, our project coordinator was particularly well placed to do. Acknowledging the emotional labour of the group was critical.

There is also a need to understand that any group’s needs are going to intersect with other ‘identities’ they may have; in our case this was focused around disability and mental health.

Another key learning point was the need for the exclusively white museum staff to acknowledge their whiteness and its unearned privileges, which can be hard and may result in feelings of guilt and defensiveness.

The group wanted time at the beginning of each meeting to talk without the presence of white people. It was important to us that the group could take their space in the museum without feeling they had to ask for it. This is one of the reasons it was so crucial to have a project coordinator from the global majority and why representation in museums generally is so important.

We also started to reconsider some of our collections, which we hadn’t previously thought to be problematic. In recent years, more research has been done on Wales’s links to transatlantic enslavement, and Welsh wool is known to have been used by plantation owners to not only clothe the enslaved, but to purchase and trade African people.

Writing the funding application in partnership with a creative practitioner from the global majority was critical to the project’s success. It gave us an opportunity to think deeply about what our needs might be and create a project that didn’t impose outputs on the group.

In fact, we were clear that producing work for the exhibition was not a condition of being part of the group, that the primary aim of the funding was to build trust and develop a lasting relationship.

Sloane’s collecting was financed in part by profits from the enslavement trade. He owned shares of plantations in Jamaica through his marriage to Elizabeth Langley Rose (who inherited them from her first husband), which means that he not only owned land but also the enslaved people whose forced labour worked the land.

He assembled his collections with the help of Indigenous and enslaved people, who he relied on for their knowledge and skills, but there is unfortunately very little information available on those he worked with. The group examined this legacy through creative responses that form a major part of the exhibition.

Sculptures of the group members’ hands, created by Déa Neile-Hopton, represent solidarity with those Sloane worked with whose stories have been lost. A compassionate letter to Hans Sloane’s wife, Elizabeth, who was just 16 years old when she went to live with her first husband in Jamaica, was contributed by Indigo Young who is of a similar age.

A short film directed by Shamira Scott, entitled Reflections: Our Words, Our Stories, Our Identities, considers the identity and heritage of the group, in contrast with the lack of knowledge about those who assisted Sloane.

A willow spiral woven by Déa with materials and techniques that originate from both Europe and Africa highlights the movement of plants and people around the world. An abstract film from artist Abid Hussain highlights his experience of feeling voiceless.

A textile work called Wake by Rose Thorn depicts the embodied pain still felt by global majority people today as a consequence of colonialism and racism. Jasmine Frater-Kinjo made paper from local poppies in response to plant matter in the Sloane collection and created portraits of participants and their children focusing on mixed-race identities.

Our project focused on the Culture, Heritage and Sport section of the Action Plan, which aims to “support all parts of the society in Wales to embrace and celebrate its diverse cultural heritage while understanding, and recognising the right to, freedom of cultural expression”.

Ceredigion Museum’s work with the Voices from the Edge group contributed to this through co-designed opportunities with the group to express their creativity, heritage, language, cultural identity and origins. They have participated in and initiated opportunities to express their own identity on their own terms and in collaboration with the museum.

Co-curating exhibitions looking at colonial legacies is hard! There are intrinsic power dynamics that must be acknowledged, very carefully negotiated, and sometimes challenged, which can create discomfort.

Managing expectations for the museum, partners and the participants is very important. Our project benefited greatly from mentoring for the museum staff, project coordinator and the participants from cultural practitioner Stephen Welsh, Maya Sharma of the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah RACE Centre and Rabab Ghazoul from Gentle/Radical.

The importance of centring global majority people in developing and delivering projects exploring colonial legacies from their inception, and acknowledging their emotional labour, is critical. Building remuneration into the budget whenever possible helps to build some equity into the power dynamics.

I would encourage an honest and transparent discussion about these issues in interpretation and displays, but there needs to be more funding available and resource to support this type of work.

We hope that this project has gone some way towards increasing representation for global majority communities in west Wales, and helped to make these communities feel welcome at Ceredigion Museum. This project has been our first step towards achieving this and we hope to continue building on this with future community co-curation and collaboration.

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.