Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

Visiting a museum can be challenging for a disabled person. Going as people with both physical and neurodivergent access needs into spaces that have traditionally been built without modern accessibility considerations can feel impossible.

We often visit major galleries and find that many of our needs appear to be overlooked or not treated as a priority.

With the National Portrait Gallery in London reopening its doors to the public in June, boasting the most extensive transformation of its building and displays since 1896, we looked forward to seeing how the project had enhanced its inclusivity in both its displays and accessibility.

In this co-written review, I (Matthew) share my experiences as a power chair user, while I (Aimée) reflect on my experiences as an autistic person while visiting the reopened gallery.

As part of the three-year redevelopment, the physical building has seen an increase in its public space available by around a fifth. It isn’t often that a museum is able to undergo such a significant redevelopment, spanning years and involving so many stakeholders. We arrived at the National Portrait Gallery with open minds and high hopes for its accessibility.

Matthew: As a power wheelchair user with muscular dystrophy, I require wheelchair access when visiting a museum. I also need enough space around exhibits to be able to manoeuvre, and for objects to be positioned so that I am still able to view them from a seated position. I would also only be able to participate in interactive displays if it doesn’t require too much reaching or lifting.

Aimée: I am an autistic woman, which can particularly impact how I experience the sensory environment within a museum. I am very sensitive to light, sound and busy spaces where it can be unpredictable.

Like many autistic people, my needs and ability to process information can vary from day to day, but I consistently find that bright lighting and echoey noises can make even known spaces feel less accessible to me.

While visiting, I was particularly interested in seeing how the gallery had adapted the space to make the sensory environment more neutral and how it communicated information on labels and signage throughout the museum.

Entering the National Portrait Gallery was simple enough; the new main entrance is ramped and the front door is wide.

The museum’s vestibule is spacious, and you are immediately presented with a combination of physical objects such as busts, portraits and interactive displays that are easy to view and set the scene for what to expect as you continue your journey into the main galleries.

From reading the promotional materials about the reopening, we knew it was worth experiencing the displays chronologically. To do this, visitors are advised to take a lift to the top.

With this in mind, it is surprising how confusing and difficult it is to navigate the lifts. There are three lifts, which don’t all go to every floor, and to access lift C, you have to pass through the Audrey Green cafe next door to the gallery. Only lift C tells you what floor you are on, but it is too small to fit both a wheelchair user and a companion.

As the floors are not obviously signposted, every attempt to use the lifts involved visitors asking each other if they were on the right floor.

The corridors for lifts A and B are too small for a wheelchair to rotate, so a wheelchair user would have to back up all the way down a narrow corridor to let someone else out of the lift.

With the lack of clear signage or announcements to indicate what floor you are on, and insufficient room to manoeuvre within and in the corridors leading to the lifts, it made for a frustrating and disorienting experience.

From a neurodivergent perspective, the new entrance to the museum felt lighter and more spacious than my memories of the previous entryway. The doors open to a series of archways where staff welcome you into the gallery, marking the transition into the museum setting.

I was struck by how well the large space was able to absorb the crowd noise, and the lighting controlled in a way that created a calmness in what could easily have become an overwhelming space.

A welcome desk, cloakroom and escalator into the first gallery clearly communicate where a visitor can start their journey, either by speaking to staff at the desk about the different audio guides and maps available, or by bypassing and going straight into the gallery spaces without needing to communicate with anyone.

We found the entry to the gallery to be one of the most successful elements of the redevelopment.

All the exhibits were amply spacious for a wheelchair user, and most of the objects and interpretation were at a good height to see from wheelchair level.

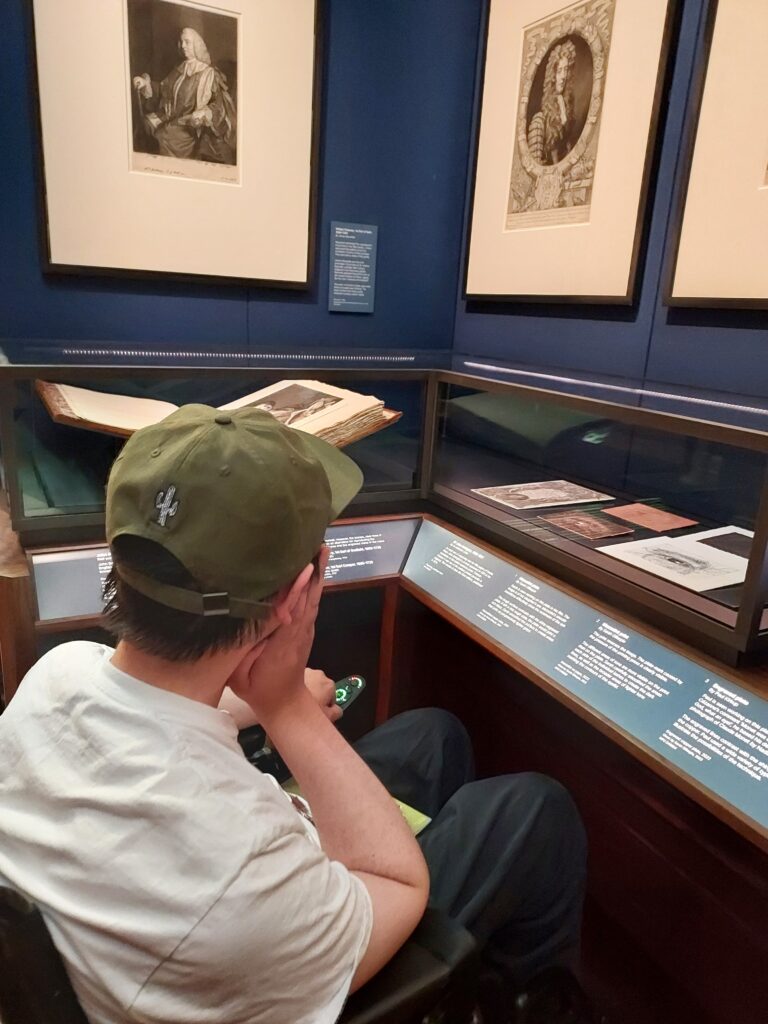

The display cabinets were designed to be high enough to get a power chair comfortably underneath, but often the angle that the objects were displayed at were too horizontal for me to see.

In some of the displays, the interpretation was published in books or on large-print handheld panels that were stored next to the display for visitors to pick up.

While this is an interesting way to communicate the information, I found that these books and panels were hard to access and heavy to hold.

Video displays are silent and the audio can be accessed through a handheld speaker you put to your ear to minimise clashing of sounds in the gallery space, but this was too low for me to reach and I wouldn’t be able to access this without help.

There is a map that offers different routes for visitors dependent on how much time they have to visit to help prioritise key objects.

Even so, navigating the galleries was often challenging due to the lack of clear signage. This continues in the gallery spaces where the numbering of the rooms often felt hidden and hard to follow.

Interpretation panels in each room did not indicate the intended direction to take, and numbering seemed to jump.

If you entered from a lift, you often began a gallery at a latter stage of the intended journey, which added to the disorientation. Some of the labels for objects felt hidden compared with others and had varying levels of detail that some may find challenging to read.

We did, however, appreciate the clear signposts to any audioguides, podcasts or digital information that visitors could access for specific artworks on display.

Many are made accessible by scanning a QR code, which also enables people to go away and process the information at their own pace.

We visited on International Portrait Day, the second official day of opening, and therefore the gallery was full of different audience groups that made navigating the space and accessing facilities challenging.

It was difficult to find quiet spaces for sensory retreat or seating away from the crowds to process the information from the visit. While the sensory environment is fairly well-controlled, with consistently bright but not overpowering lighting, and walls with fabrics to absorb the sounds, it is likely to continue to be crowded in a way that could be overwhelming.

We felt that clearer signage and signposting would help with the flow around the galleries. It would make it easier for people to find quiet spaces quickly and would enhance the overall experience of visitors.

While the National Portrait Gallery has undergone significant work to increase the inclusivity and diversity of its displays, with particular focus on increasing the visibility of women and ethnic minority sitters, we both felt that disabled histories and representation opportunities were missed.

There are approximately 1,100 portraits on display at the gallery. Considering disabled people make up 17% of the population in England (according to the 2021 census), there is a paucity of representation in the exhibits.

We counted five portraits of disabled people, four of whom were male, all of whom were white, and all of whom were physically disabled on display. There was also no noted representation of any neurodivergent or “invisibly” disabled sitters on display.

While we had expected there to be a gap in representation of disability in the Tudor-Victorian gallery spaces, which contain no disability representation, we were shocked that there were still minimal portraits of disabled people in the contemporary galleries.

In particular, we did not find one disabled sitter in the Weston Wing, which covers the years 2000 to today.

And of the artworks on display that do portray disabled sitters, we found that they often seemed hidden away. In particular, we discovered the stunning portrait of Dorothy Hodgkin in a concealed corner.

There have also been opportunities missed to include a disabled perspective in the interpretation.

For instance, there is a display dedicated to world war one, an event that left some of the largest numbers of people in history disabled, but no mention is made of this vital narrative in understanding the impact of this war.

Similarly, though figures such as the 18th-century writer Dr Johnson are displayed, the interpretation does not mention his well-documented physical disability.

While we were very impressed with the efforts made to address other underrepresented or misrepresented groups, we left the gallery feeling that disabled people like ourselves had remained hidden.

It is clear that the National Portrait Gallery has been transformed in its redevelopment.

We were very impressed with many of the architectural and interpretive changes, particularly with the new entrance, Changing Places toilet facilities, increased display space and the sensory environment.

Even with its aim to increase inclusivity and reinterpretation, however, there are still clear areas where accessibility and disability representation could be improved.

The signage, lift accessibility and physical accessibility to the interactive components are all areas that would benefit from further consultation with disabled people.

We would also love to see the gallery work with disabled people to address the underrepresentation of disability on display as part of its ongoing work to engage audiences.

Aimée Fletcher is an autistic PhD researcher at the University of Glasgow, studying how to make museums more accessible to neurodivergent people

Matthew Hayhow is a disabled freelance culture journalist based in Glasgow, and has previously done digital work experience for the Scottish Fisheries Museum in Anstruther

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.