Enjoy this article?

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

On a warm and breezy July morning last year I stepped through the Grace Gates of Lord’s Cricket Ground in London’s leafy St John’s Wood for the first time in over 20 years.

The time before was either a Middlesex CCC county match disintegrating into a turgid draw or when I was attending the MCC (Marylebone Cricket Club) Indoor Cricket School, I can’t quite remember.

This time I was there to attend the formal launch of a major new exhibition called No Foreign Field: MCC and the Empire of Cricket and to talk museums, public history and culture wars, as part of a panel in an eponymously named symposium taking place that day in collaboration with the University of Leicester, which was a co-curator of the exhibition.

The No Foreign Field symposium wove together debate between sports historians, pundits, MCC members, cricket fans and curators and was a thoroughly stimulating example of well-considered speaking following well-considered thinking.

I would have never expected a discussion about critical race theory at somewhere like Lord’s with its 30-year membership waiting list, Panama hats and egg-and-bacon ties, but it happened, thanks in part to journalist Peter Oborne’s lightning provocation and a magisterial exposé of the problem of how and who writes about cricket by sports write and novelist Arunabha Sengupta.

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

Quite honestly this was the most interesting and exhilarating event addressing colonial legacies I have taken part in.

Prashant Kidambi, historian at the University of Leicester, and Neil Robinson, head of heritage and collections at the MCC (Marylebone Cricket Club), spearheaded the symposium and the exhibition.

I was reading Kidambi’s Cricket Country (Oxford University Press, 2018) prior to reviewing the new exhibition – its premise being “cricket is an Indian game accidentally discovered by the English”.

Detailed insights into the complexities and contradictions of early Indian cricket tours to the UK, and especially of the rivalries, camaraderie, mutual support, dirty tricks and prejudices between colonial and “native” teams in India during the age of empire made me look forward to seeing how these would be portrayed in an exhibition format. My expectations were high.

The exhibition has pride of place and total centrality at the MCC Museum and it will do for another two years. Last year marked a transformational year at the MCC museum with the launch of four new exhibitions and redisplays.

As well as No Foreign Field, there is a redisplay of notable batters and bowlers, now much more international and somewhat more reflective of the women’s game – this is on the ground floor where the original Ashes urn is guarded; Tom Shaw’s beguiling portraits of England’s Black Cricketers alongside Mark Butcher’s Sky documentary, The Story of England’s Black Cricketers: You Guys are History (check it out on Sky Sports Cricket’s YouTube channel); and the inaugural exhibition in the community-curated gallery Cricket and the Jewish Community, which I found particularly immersive as co-curators Zaki Cooper and Daniel Lightman avoided the pitfalls of an over-arching narrative and instead provided a series of well-written vignettes on Jewish and supposedly Jewish cricketers and others involved in the game.

At the very least, one of the most imperial of institutions deciding to stage an exhibition to, at least partially, examine its own colonial legacies while also organising three compelling key exhibits on usually marginalised subjects ought to be applauded.

A simple run of panels takes visitors on a chronological promenade through the changes affected on the MCC and world cricket from the late 19th-century world of gentlemanly amateurism to the present day of fully franchised club cricket of the type now centred in the Indian Premier League (IPL) and fully inclusive of women (we only had to wait until 1998).

Much of the MCC’s collections are archival and it was heartening to see so many letters and albums on display alongside hallowed artefacts such as match-winning cricket bats, balls, flags and autographed shirts. These things are not easy to display in a way that is visually pleasing and accessible but the curators and designers have done an excellent job.

Additional information on exhibits is provided on screens and headphones can be used to enjoy audio and video snippets. There is something about archival audio that immediately creates an environment you feel connected to.

My favourite exhibits are conveniently displayed side by side: one is from the 1868 Aboriginal tour of England, “Dick-a-Dick’s leangle” (a type of boomerang) used by Jumgumjenanuke (his real name) to defend himself from cricket balls being thrown violently at him by English players and officials, who paid for the privilege in a post-match entertainment segment (he defended every ball).

My other favourite is the team portrait of “The Parsees”, the first Indian team to tour the UK in 1886, posing in dapper Western wear but all with topis (caps) typical of Parsi “Sunday best”.

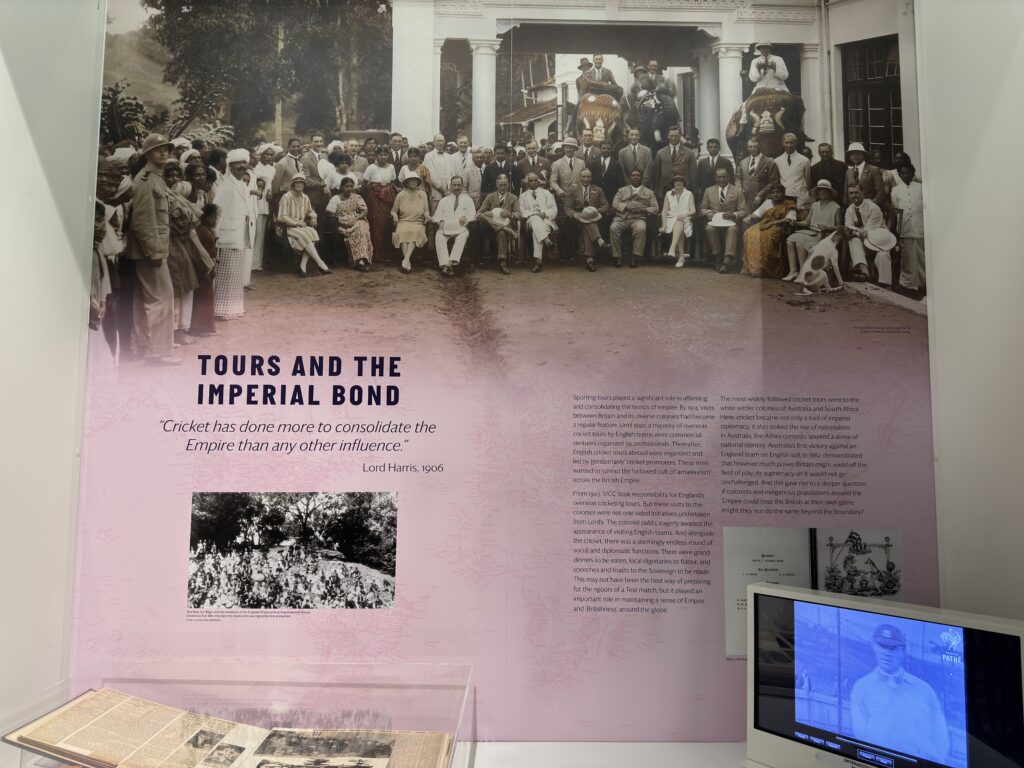

Unlike the Jewish cricket exhibition, the No Foreign Field curators dared to go for the over-arching narrative as its thematic backbone, starting with “first contact”, through to the “imperial bond”, “conflict” and the “MCC today”.

While the interpretation was in no way triumphalist (the benevolent empire) or glorifying (look at the good things we did), and packed full of well-researched and referenced information, I was left mildly frustrated by some of the framing of the narrative and individual interpretation.

In the introduction, the colonisers had occupations: soldiers, saliors, administrators, educators, but the colonised were simply “local populations”.

The tired trope of colonisers encountering an amorphous lump of locals when writing about empire needs conscious effort to avoid. We have the research and information – much of it is in Kidambi’s book – so why not use it?

I was especially disappointed that the gripping and often hilarious story of the various attempts by Parsi cricket clubs to claim space in colonial Bombay, and to get an international tour off the ground, was not used as a classic example of how it is impossible to be simplistic about colonialism or its effects on all concerned.

Similarly, we are promised “nuance and shades of grey” but they are rarely expressed in the detailed storytelling. Instead, there are pat narratives of well-documented named white colonial figures, such as Sir Abraham Bailey, also known as “Rhodes the second”, while discussion of the impact those people had on those colonised are omitted. Again, this information is well-documented and easy to find.

This is an ambitious exhibition given its context, and promises cricket and empire history fans alike a really good insight into how an institution such as the MCC threaded its way into the corridors of imperial power, and vice versa. I recommend booking onto a tour and visiting this little-known small museum.

No Foreign Field closes in March 2026. Tickets are included in tour bookings, and entry is free on major match days. There is a small charge on MCC and Middlesex match days

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.