Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

Sgeul is Scottish Gaelic for the word story. It is also the title of the National Library of Scotland’s first dual-language exhibition, presented in Gaelic and English. Gaelic comes first in the text, indicating its primacy in this context.

Subtitled “Folk Tales from the Scottish Highlands”, the exhibition focuses on the collecting activity of one man, 19th-century folklorist John Francis Campbell. As such, it is less about the actual stories, more the process of their preservation, resulting ultimately in their presence in the library’s collections.

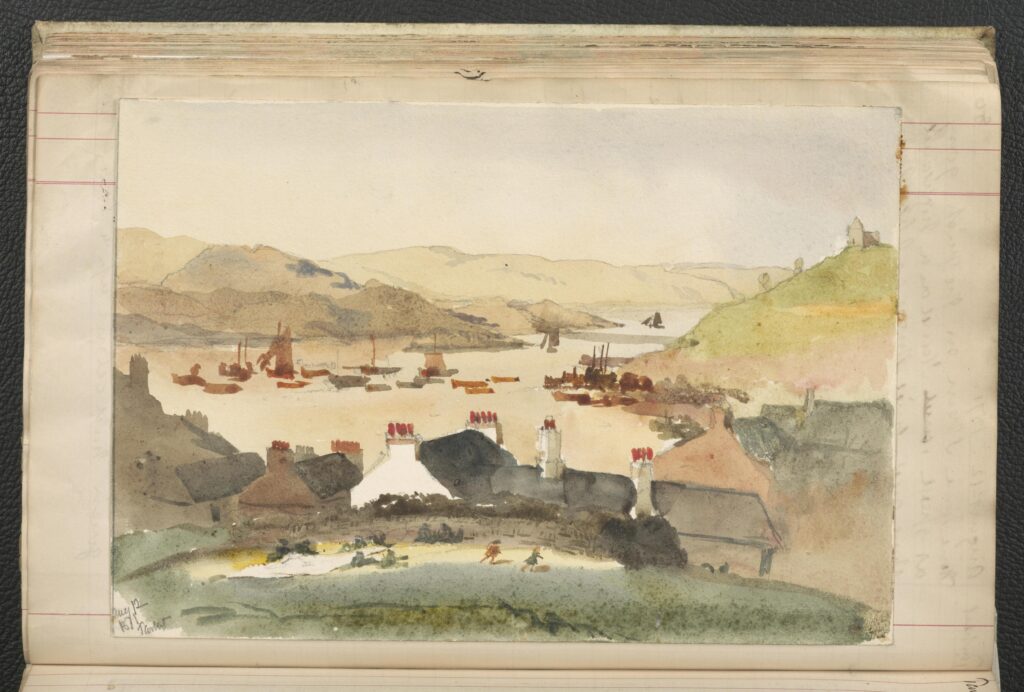

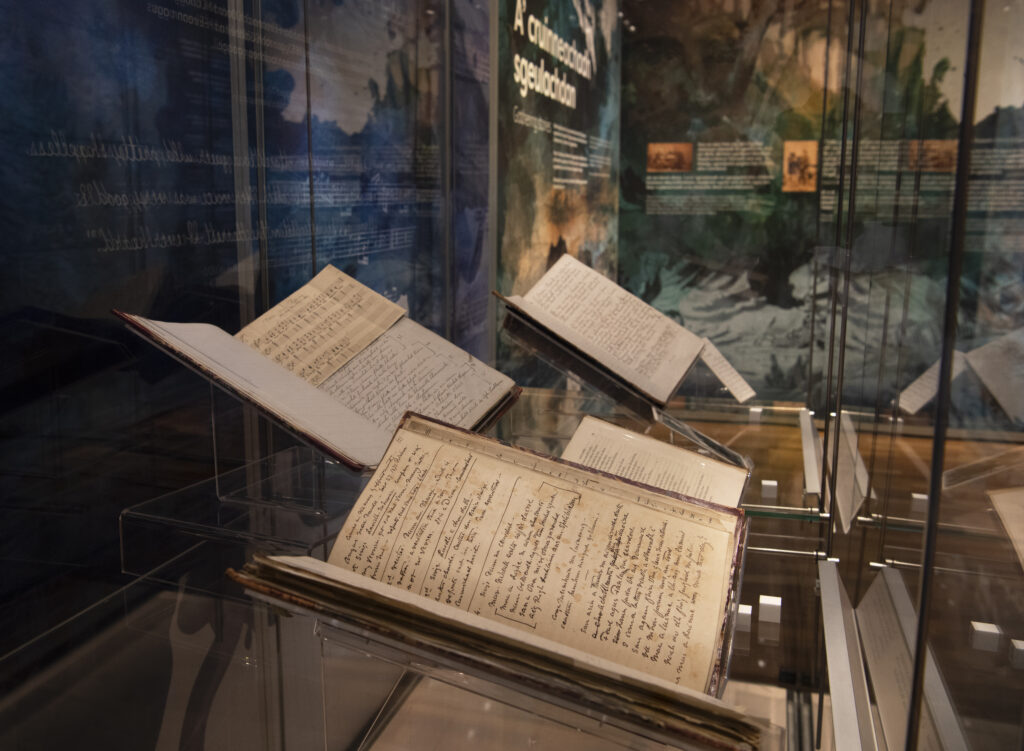

The material displayed in the main body of the exhibition is drawn from the library’s archive of Campbell’s manuscripts and includes correspondence, diary notes, transcribed stories, sketches, illustrations and watercolours. The stories themselves are brought to the fore in other ways in the latter stages of the show.

Brought up on Islay, Campbell began collecting Scottish Gaelic folk tales in 1859. The Gaelic tradition was largely oral at that time, and so the act of collecting was more akin to recording or capturing stories handed down through generations, visiting locations and communities across the Highlands and Islands.

One of the difficulties in presenting an exhibition largely comprised of written material is that the core display is words, and most additional interpretation is, well, more words. It is understandable therefore that the use of text is relatively sparing.

The exhibition does a good job within those parameters of explaining Campbell’s methods, travels and encounters with a rich tapestry of characters, while evoking the otherworldly beauty of the Western Isles as well as the occasionally harsh realities of island life.

Manuscripts, while evocative, can be hard to read and so there is the welcome addition of a bound volume of large-print transcripts.

The National Library of Scotland’s grand frontage dominates the north end of Edinburgh’s George IV Bridge, but there’s only one small double-doored entrance, representing its historic exclusivity. In recent years, there has been a marked change towards greater accessibility.

This includes two wheelchair lifts in the entrance to take visitors up from the street-level entrance to the main foyer. From there, it is level access through to the exhibition.

There is a large set of heavy, manually operated double-doors at the gallery entrance and, as far as I could see, no particular staff presence in the immediate vicinity. However, the information desk is staffed and I would expect any visitor requiring assistance to be supported on arrival.

The exhibition has been produced collaboratively between library staff and experts from Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the National Centre for Gaelic Language and Culture, which is part of the University of the Highlands and Islands. Accordingly, Sgeul represents not just the Gaelic language, but also perspectives and identity.

There are a couple of instances where a little more context might have been useful. Specifically, the exhibition asserts that Gaelic storytelling was “dying out” by the mid-19th century, but it does not address why this was the case.

Admittedly, that is not an easy topic to cover succinctly, and it may well have been a deliberate decision not to go there. However, I do think there could have been some reference to the factors that affected the Gaelic-speaking communities of the Highlands and Islands in the preceding century.

The connection between Gaelic folk tales and those of other cultures was another intriguing theme that could have been further developed outside passing references to the Brothers Grimm and Arabian Nights tales.

For example, Campbell’s extensive travels beyond Scotland are referenced alongside beautiful watercolours created during visits to Scandinavia. The exhibition misses a beat for me here in not spelling out why a Gaelic folklorist would seek comparable tales there.

The islands of Scotland were for centuries an integrated part of a Norse seafaring network that included Ireland. The Western Isles remained at least nominally part of Norway long after the end of the Viking age in the rest of Britain, and that connection is a significant part of the region’s distinctive history and cultural legacy.

The mythical selkie – a half-human, half-seal creature – is just one example that springs to mind of a story that recurs across Norse, Irish and Scottish folk tales.

The final sections move beyond Campbell’s biographical story and away from conventional case displays. One measure of success for a historical exhibition is the extent to which it acts as an inspirational launchpad into further reading and learning. In Sgeul, you can do so right there in the gallery.

In an interactive, family-friendly area, more than 50 books are presented alongside comfortable seating, offering a tempting invitation to increase one’s dwell time.

This includes four volumes of Campbell’s own 1862 publication, Popular Tales of the West Highlands, as well as a host of folk tale compendiums for both children and adults.

There are also titles offering contemporary reinterpretations of the tales from alternative perspectives, such as Wain: LGBT Reimaginings of Scottish Folk Tales by Rachel Plummer, and Karrie Fransman’s Gender Swapped Folk Tales.

And visitors can listen to a selection of stories via a listening post with readings in English and Gaelic, and create tales of their own through a set of “story dice”.

The exhibition concludes with a film, which is part summary of the past presented in the exhibition, a brief reflection on Gaelic storytelling today and, through footage of pupils from Bun Sgoil Taobh na Pairce, Edinburgh’s Gaelic Medium Education primary school, a glimpse of its potential future.

The overall verdict, then, is “chan eil dona idir”. My daughter, who goes to the aforementioned Gaelic school assures me that translates as “not bad at all”. Which, if you’ve ever hung out with a certain sort of Scottish person, you’ll know translates to “actually, that was pretty good”.

Bruce Blacklaw is the communications manager at National Museums Scotland

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

You must be signed in to post a comment.

The reviewer mentions that the manuscripts can be hard to read but what of the exhibition text? Any accessibility guidelines will tell you that poor contrast and busy backgrounds are a no, no.