Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

One of the most visited art exhibitions in history was the brainchild of the Nazis. Touring Germany between 1937 and 1939, Entartete Kunst (translated as “Degenerate Art”) combined famous contemporary art with works by mental asylum inmates.

Developed by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler and his minister of propaganda Joseph Goebbels, the exhibition was key to a cultural programme to convince citizens that modern art was symptomatic of a degenerating culture and race, and in need of wholesale refashioning to build the new German state.

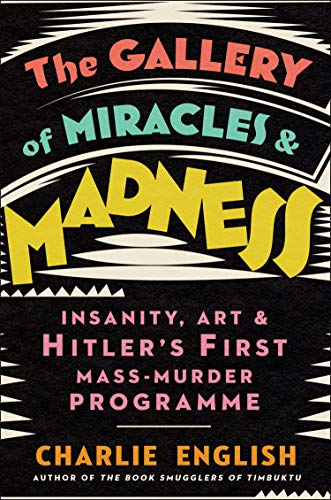

Charlie English’s book, The Gallery of Miracles and Madness: Insanity, Art and Hitler's First Mass-Murder Programme, tells the compelling but traumatic story of how art, medicine and politics came together between the two world wars, horribly combined into an ideology that would ultimately justify mass murder. This is, at its heart, the story of an art collection.

From 1919 in the university town of Heidelberg, Hans Prinzhorn, a trained art historian and qualified physician, built a collection of extraordinary artworks produced by asylum inmates. He brought the works to the attention of a contemporary art world already questioning how art could respond to the trauma of the first world war.

Dada and surrealist artists such as Max Ernst, André Breton, Salvador Dalí, and Hugo Ball saw “insane” art as untainted creativity, seeking to capture its essence by drawing inspiration from Prinzhorn’s collection.

Yet Prinzhorn also brought the collection to the attention of cultural conservatives and rival physicians such as Wilhelm Weygandt, who had his own collection of “insane” art. However, he argued that similarities between these works and modern art showed contemporary “degeneracy” of thought.

Such ideas became woven into National Socialist ideology and particularly Goebbels’ campaigns, through which he would mould the nation through art and politics, with healthy art equating to a healthy race.

Hitler held two exhibitions in Munich in 1937. Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (or the Great German Art Exhibition) displayed approved German art, and represented what the Nazis perceived to be the ideal German citizen.

By contrast, Entartete Kunst showed “degenerate” modern art, in which, to Hitler’s eyes, artists either mis-saw or purposely misrepresented people.

As it toured Germany, the exhibition was expanded to show works from Prinzhorn’s collection as comparisons. The accompanying booklet called on citizens to consider which work was more “mad”, and what threat these artists “both sane and insane” might pose to society.

The destruction of collections across Germany followed, alongside the secret development of a forced sterilisation, and then murder programme, to rid the state of both artworks and people “unworthy of life”.

Thankfully, English makes this a story of people as much as artworks. He threads the stories of the inmates behind the works, putting their medical histories, successes, and interests alongside those of figures such as Prinzhorn, Goebbels and Hitler.

A major character is Frank Karl Bühler, whose ironwork won first prize for Germany at the Chicago World Fair in 1893. A likely schizophrenic, he was sent to Emmendingen asylum in 1900 and was murdered at Grafeneck Castle killing station in 1940. English follows his life, highlighting his extraordinary work Der Würgengel (The Choking Angel), featured in Entartete Kunst, and hailing his inclusion in the new Prinzhorn Museum at Heidelberg in 2001.

The Gallery of Miracles and Madness is beautifully written but necessarily hard to read. English’s story ultimately speaks of the power of collections – in the right or wrong hands – and of the importance of how they are interpreted, of how culture and politics shape each other, and of the power of creative expression.

Katy Barrett has worked with a number of national and university collections and has higher degrees in history of art and history of science. She is the deputy chief curator and head of engagement at the Houses of Parliament

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.