Enjoy this article?

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

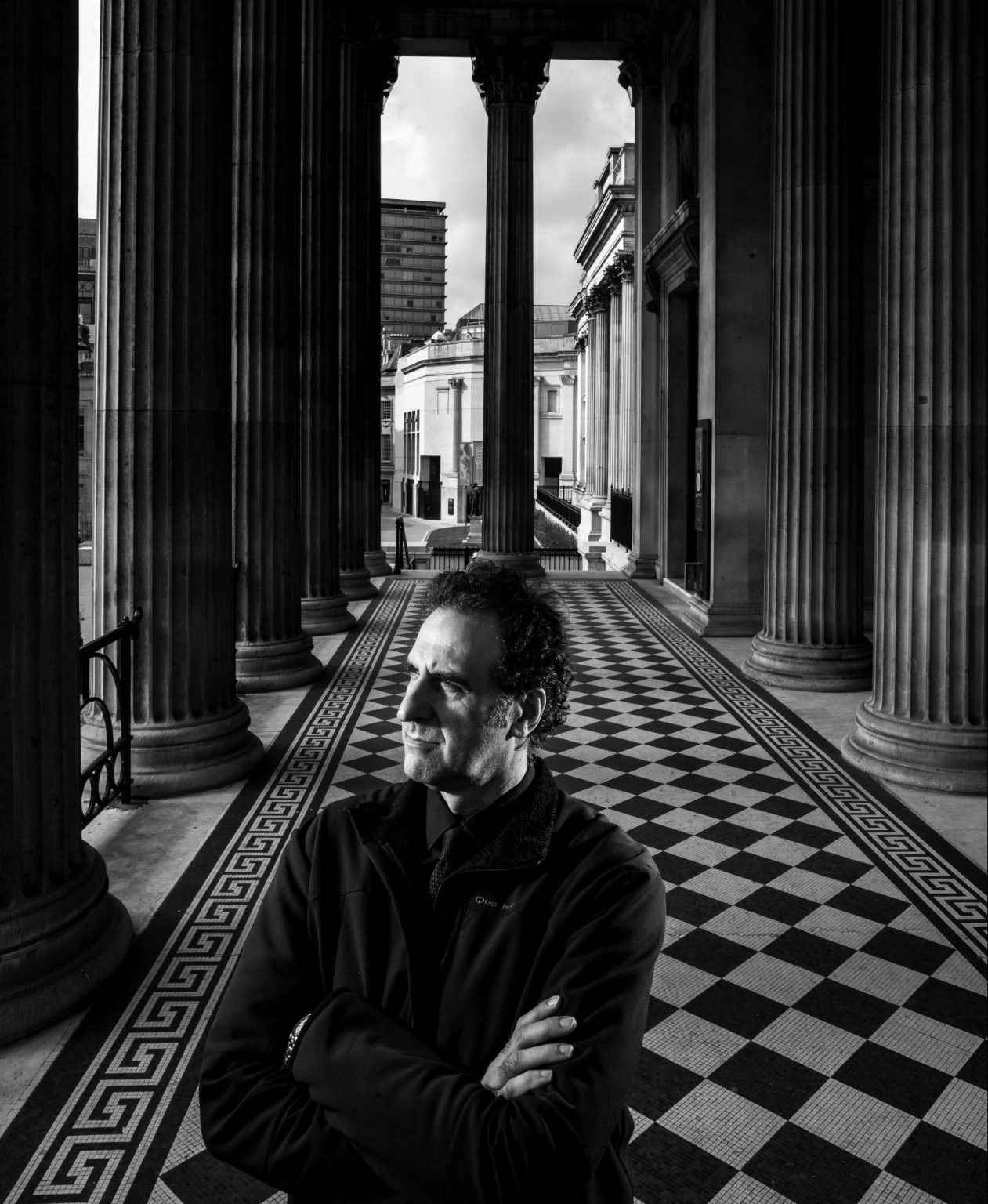

Gabriele Finaldi is one of those lucky people who not only knew what they wanted to do from a young age, but has been able to successfully follow that interest throughout their career. The director of London’s National Gallery grew up in Catford in south London and says art was very much part of his life, with his parents interested in painting, music and literature.

A key moment was encountering Rembrandt’s Girl at a Window at Dulwich Picture Gallery, which happened after he left comprehensive school to take up an assisted place at Dulwich College.

“It was a moment of revelation,” he says. “Aged 16, I thought that I really wanted to devote myself to the arts and I’ve been very fortunate that this has been possible.”

Gabriele Finaldi

Gabriele Finaldi has been the director of the National Gallery since 2015. He was previously the deputy director for collections and research at the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, a position he took up in 2002. Prior to the Prado, he was a curator at the National Gallery between 1992 and 2002 where he was responsible for the later Italian paintings in the collection (Caravaggio to Canaletto) and the Spanish collection (Bermejo to Goya). Finaldi was born in London in 1965 and studied art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

Finaldi later studied at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, before joining the National Gallery as a curator in 1992. Former British Museum boss Neil MacGregor was the director of the gallery at the time and was raising the profile of the institution. Finaldi spent 10 years there before heading to Madrid in 2002 for a role at the Museo Nacional del Prado.

“That was certainly a very exciting moment in my career,” he says. “The Prado was undergoing pretty major changes – it was becoming a bigger institution and more professional and it wanted to play a more important role on the international stage.”

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

Finaldi remained happy and fulfilled in his role as the director of collections and research at the Prado, but in 2015 he was offered the chance to return to London and rejoin the National Gallery as its director.

“It was a wonderful opportunity – I love the National Gallery deeply,” says Finaldi. For someone who cares so profoundly about an organisation, the past year has been challenging as he has battled to steer the gallery and its staff safely through the pandemic.

“It’s been very tough for us,” he says. “Financially, we have been hard hit, like all museums. The gallery depends on self-generated income of up to nearly 50% of revenue, and a lot of that has gone because it is from our shops, restaurants, exhibition ticket income and event hire. All of that has been very seriously affected.

“The model that we operate under is one that requires large numbers of people to visit,” he continues. “Well, that didn’t happen last year and I think it’s going to be very, very slow this year as well.”

Finaldi says staff morale at the gallery has remained high and the organisation has not had to furlough any directly employed staff or make anyone redundant.

Like most other large art museums around the world, temporary exhibitions are vitally important for the National Gallery in attracting visitors and generating revenue. Its whole programme had to be reworked because of the pandemic, including postponing a Raphael show being staged last year to coincide with the 500th anniversary of the death of the Italian painter.

The gallery was also hugely disappointed that it was forced to close its Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition having put so much effort into promoting the 17th-century female artist and her work. This included a pre-lockdown national tour of a Gentileschi self-portrait that the gallery acquired in 2018 and Finaldi is proud of the fact the work visited a number of unusual venues for old master paintings, including a prison, GP surgery and a school.

“We had created a real buzz around Artemisia but in the end it was only open for about six weeks,” says Finaldi. “You lay your plans very carefully, as exhibitions involve a whole host of elements, partners, people, contracts, relationships and so on. When the pandemic came along, suddenly all of that had to be reworked very rapidly.”

National Gallery, London

London’s National Gallery was founded in 1824 and its current building was opened on Trafalgar Square in 1838. The gallery houses paintings from the late-13th to the early-20th century. This includes classic works such as George Stubbs’ Whistlejacket (top left) and Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (above) as well as works by renowned artists including Degas, Monet, Raphael, Rembrandt, Turner and Velázquez.

The Sainsbury Wing opened in 1991 to display the entire early Renaissance collection. Previous directors include art historian and broadcaster Kenneth Clark (1934–1945), former British Museum boss Neil MacGregor (1987–2002) and Charles Saumarez Smith (2002–2007), who went on to be chief executive of the Royal Academy of Arts from 2007 to 2018.

The last time that the National Gallery was disrupted for so long was during the second world war, when the whole collection was moved to safety elsewhere in the UK.

But with cultural institutions shut across London, it hosted lunchtime concerts during the conflict, which drew huge numbers of people. Eighty years later, the gallery was one of the first to reopen after restrictions were eased last summer.

“We opened on 8 July, the earliest possible date after the first closure,” Finaldi says. “We were just really keen to get people back in. We used the strapline about returning the nation’s pictures to the nation and there was that sense of public responsibility.”

The public’s passion for returning to museums was one of the positives of the pandemic for Finaldi, as was the way that the sector pulled together.

“The pandemic brought out a lot of solidarity between museums – we are all very keen to help one another,” he says. “And we’ve never been in such close contact with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), which is our sponsor body, and I think the arts council has been on top of the situation. It’s about the money as well, and I think DCMS has been very successful in negotiating a strong package for the culture sector.”

For the National Gallery, earlier investment in its digital work, a priority for Finaldi when he became director in 2015, paid dividends during lockdown when the institution joined the rest of the sector in looking for new and interesting ways to engage audiences online.

“Suddenly you’re no longer a physical gallery, you’ve gone exclusively online,” he says. “We were in a strong position to do that and it was hugely appreciated.”

Finaldi points to the positive reception to One Painting, Many Voices, an online initiative that allows people to say what paintings in the National Gallery collection mean to them. He also says that his team has had lots of success with online teaching and lectures, which the gallery is looking to build on after the pandemic has ended.

“There’s a real opportunity for monetising our digital presence,” Finaldi says. “Our education courses used to be limited by the number of people you could fit in the lecture theatre, but that’s no longer the case. They can be much, much bigger and there are real opportunities there.”

With things starting to feel like they might eventually return to normal, Finaldi is looking to the future, particularly the gallery’s plans for its bicentenary in 2024. This will include a range of exhibitions and outreach programmes around the UK and the world under the banner NG200. It will also include work to improve the welcome from Trafalgar Square, including reconfiguring the ground floor at the Grade I-listed Sainsbury Wing to upgrade the visitor amenities and create new spaces.

The NG200 plans are part of Finaldi’s strategy to develop new and innovative programmes while not forgetting the gallery’s history and traditions. But this does not mean ignoring current issues, whether that is the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement, social injustice or tackling the climate crisis.

“Museums have to share societal concerns – we can’t stand aloof,” Finaldi says. “Maybe that was the position museums sometimes took in the past, but now museums are much more concerned about engaging with contemporary social and cultural concerns. Like other museums, we have been looking very carefully at our own institutional history and in particular the links with slavery.”

Finaldi also wants the National Gallery to appeal to a wider range of people. He acknowledges that many art museums have traditionally been the preserve of a certain element of society, and accepts that they need to find ways to broaden their audiences, programmes and workforces.

“I am very keen that the gallery opens up to new and different voices,” Finaldi says. “The traditional model of the art gallery was that it belonged to the curators and they were the people who spoke about it. That’s changed quite radically over the last generation and we’re all much more conscious in public museums that there are many voices that can speak about a gallery.”

One of the ways that Finaldi is broadening the gallery’s appeal is through contemporary art. “There is an intersection with what we do now and the historical mission of the gallery,” he says.

“The gallery was intended to be an inspiration for contemporary artists, right from 1824. They didn’t quite use those words but effectively that’s what it was. So the gallery should continue to impact positively on contemporary artistic life – that is very important.”

The National Gallery recently announced a collaboration with Kehinde Wiley on an exhibition of new work this winter. The US artist is best known for his portraits that render people of colour in the traditional settings of old master paintings. Most famously, he was commissioned to paint Barack Obama, becoming the first Black artist to create an official portrait of a US president.

Research is another key concern and a new research centre is being developed as part of the NG200 plans. This is likely to be housed in the historic Wilkins Building.

“Research is absolutely fundamental,” Finaldi says. “It’s about the scientific research, collaboration with other institutions and bringing in different disciplines and different approaches to enrich your own research. All of that has to be the basis of the way we operate otherwise we will become an increasingly superficial organisation. And we’re talking about research for public benefit. It’s not ivory-tower research, it’s research that flows into the way the gallery communicates with the outside world.”

The pandemic severely hampered the way that the gallery communicates with audiences so Finaldi is excited by the return of visitors. He is also eager to return to museums himself.

“I’m really keen to go back to the Horniman, which was my local museum when I grew up,” says Finaldi, who still lives in south London. “I want to see the musical instruments and the walrus.”

With visitors at last returning to museums and galleries all over the UK, Finaldi can start to focus again on what he sees as the core aim of the National Gallery – bringing art and people together.

This area of Museums Journal is normally just for members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.