Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The importance of taking an unflinching look at African-American history to help create a shared future

For more than 100 years, a national museum devoted to the African American experience existed only in the mind’s eye. The dream first began when Black civil war veterans raised money to create a monument in Washington, DC, to honour Black soldiers.

That dream continued to coalesce with support from luminaries and legislators, such as Mary Church Terrell and John Lewis. It eventually took root with African Americans everywhere who wanted to celebrate the legacy of a people who profoundly shaped our country.

In 2005, it became my responsibility to make real that dream when I was appointed founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

When the daunting work of bringing the museum to life began, it was a museum of no: no staff, no site, no collections, no money. And no shortage of challenges to overcome, from the need to raise $250m to the discovery that upsetting the water table underneath the museum could topple the Washington Monument, a decidedly bad thing to have on one’s résumé.

What I did have was the determination that the museum would dive into the currents of race that run so deeply in American society. It would shed light on the dark parts of our history and celebrate the joyous moments. It would explain how the events of the past continue to shape our present. And it would be a museum for all, using African American history as a lens to better understand what it means to be American.

One can tell a great deal about a country not just by what it remembers, but by what it chooses to forget. In the United States, our tortured racial past is our great taboo. Despite the preference by so many to forget, I knew that for the museum to succeed it would need to look unflinchingly at that history.

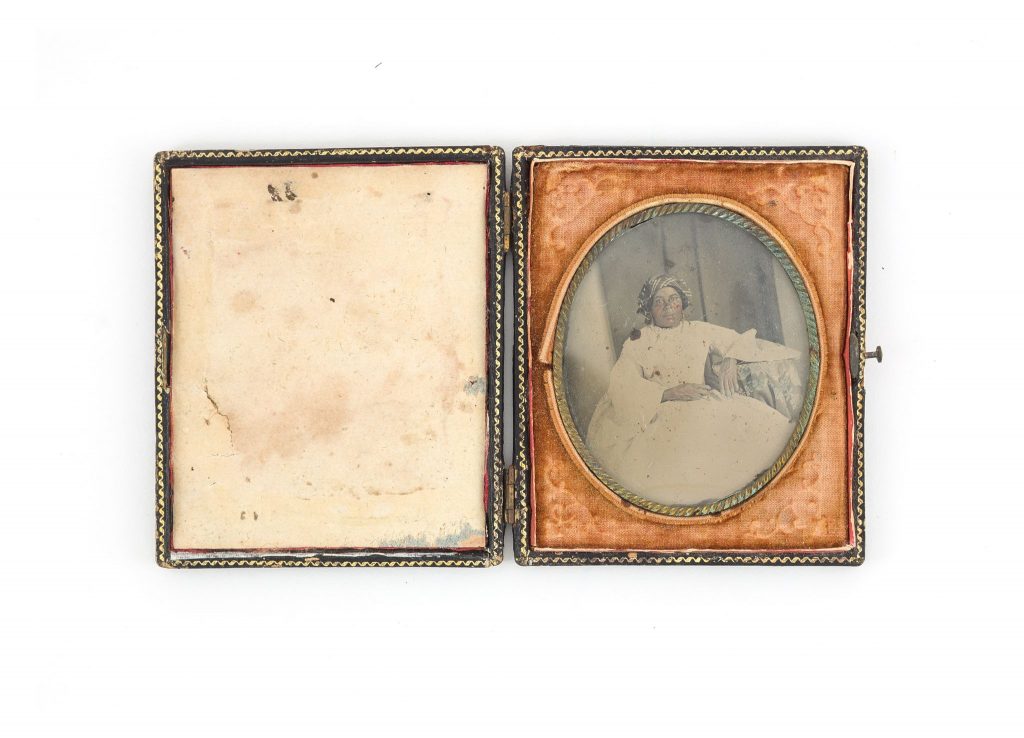

We sent experts across the country to help African Americans protect and preserve the artefacts, mementos and keepsakes tucked away in their attics and closets in the hope they would consider donating some of them to us.

It sometimes seemed like the families who had cherished these objects for decades had done so in anticipation of the day when the museum would finally open to the public.

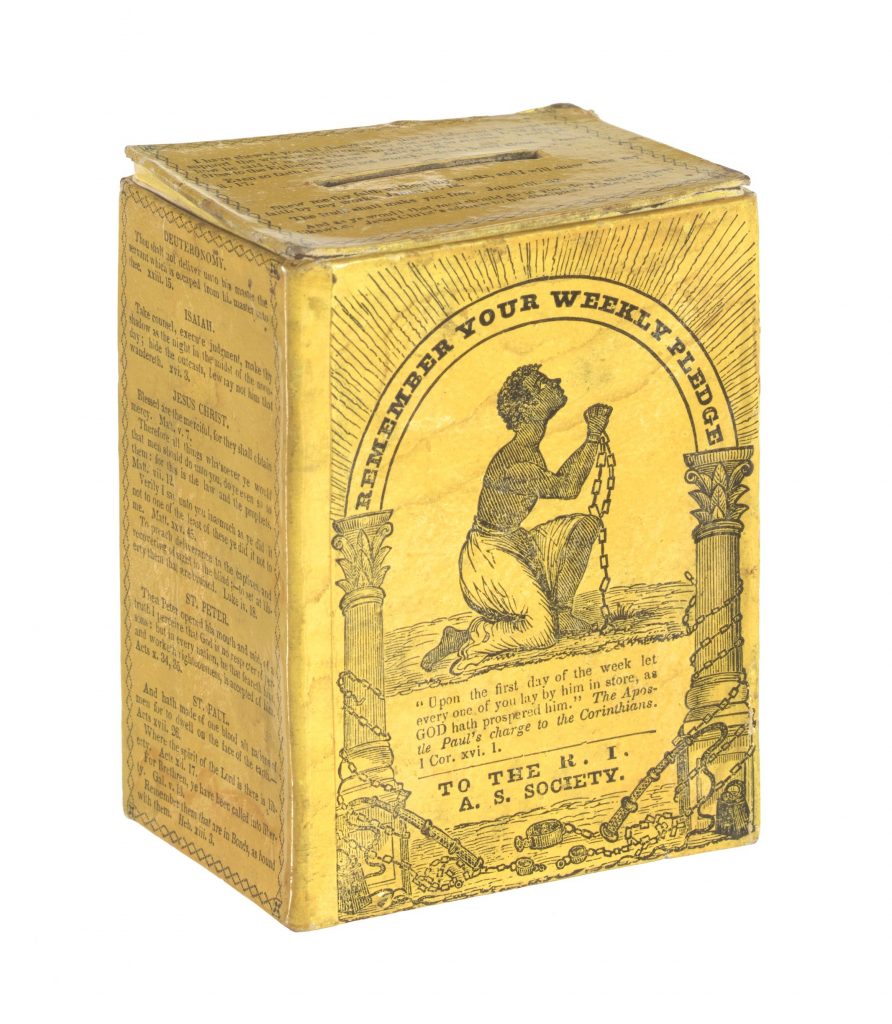

From Harriet Tubman’s shawl to the handmade tin wallet a man carried with him to protect his freedom papers after emancipation, the invaluable additions to our collections validated our community-centred approach.

In addition to its historic objects, the museum itself is imbued with powerful symbolism. Its prime spot on the National Mall proclaims that the rich African American narrative told within is as American as that told in any museum.

The museum’s design also tells a story, its exterior echoing the corona shape prevalent in Yoruba art and referencing the iron work of enslaved labourers in New Orleans and Charleston. The very existence of the museum exemplifies the efforts of a people to persevere and to challenge the nation to live up to its ideals.

In the years since the museum opened, its ability to convene serious discussions has proven to be vital. There persists a concerted effort to rewrite history into a more comfortable narrative.

The killing of George Floyd and the subsequent demands for justice remind us to never avert our eyes from the hard truths about racial inequities. As cultural institutions, it is our responsibility to be honest brokers of history and to lead conversations about how best to move forward as societies.

The good news is that new generations are embracing our unvarnished history, from Juneteenth (a federal holiday in the US that commemorates the emancipation of African-American slaves) to the Tulsa Race Massacre (which occurred in 1921 when white residents mobbed and attacked Black residents).

It is more crucial than ever that cultural institutions help tell these stories, not just in the United States but around the world. The Black British Museum project and others joining in the hard work of interrogating our past, good and bad, are vital tools of understanding and advancing our shared future.

A quest to uncover untold stories and why we need heritage workers to ensure all voices are heard

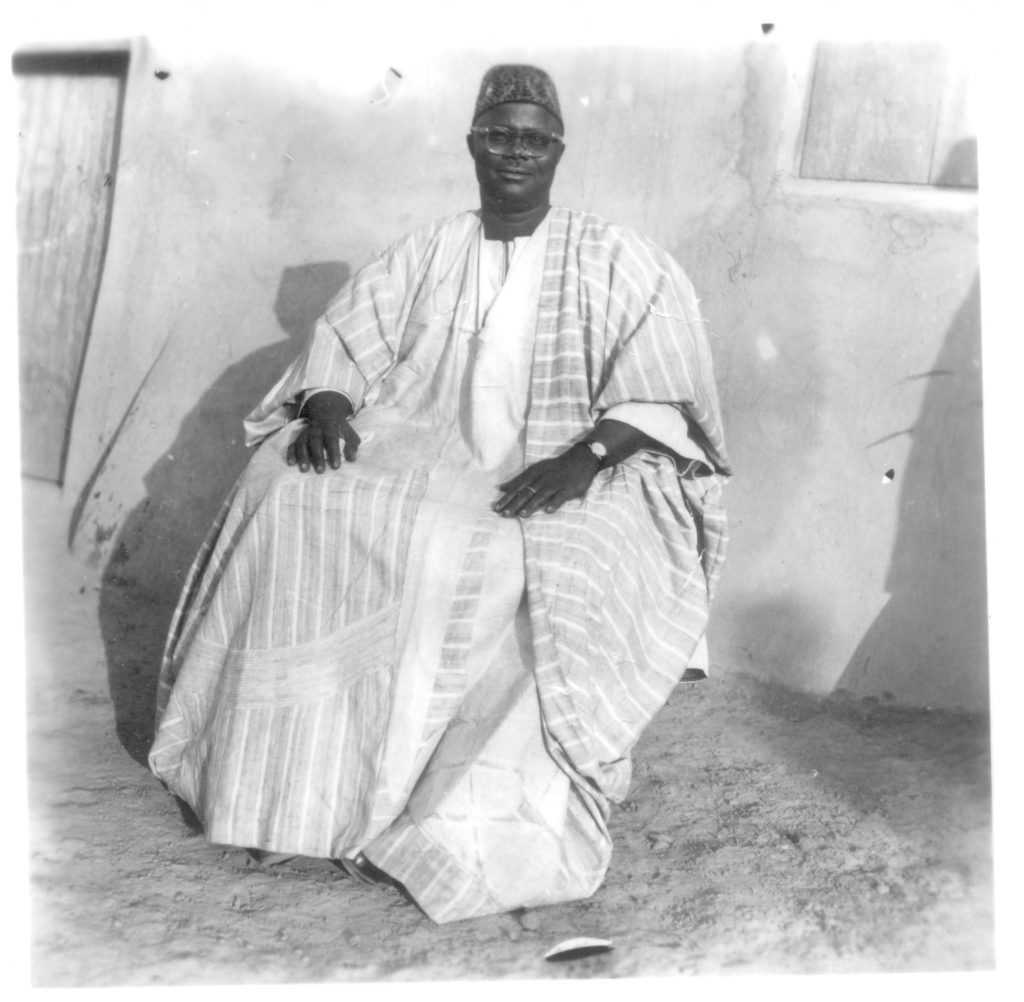

I would like to begin this account with a photograph of an unidentified chief from Nandom, Upper West Region, Ghana.

The photograph immediately caught my attention. Even seated, his appearance was imposing, though the slight smile that barely escaped his lips gave him a hint of gentleness.

The “agbada” that draped him suggested a man of stature. Who was he? The brief Information Services Department Photo Library description simply said: “Nandom chief, 1980s.” However, I knew I would use the photograph in the exhibition catalogue, but I would have preferred more information for the caption. Unbeknown to me, that photograph would go on to generate much reflection about Black memory work and practice, and we even found out his name.

I was curating Tapestries of History: Cultures and Traditions of the Upper West, an interactive and participatory project designed as part of the activation of the Nubuke Foundation’s Clay and Textile Centre in Wa, the capital of Ghana’s Upper West region. Nubuke Foundation is a visual art and cultural organisation that serves as a nexus for arts and culture in Ghana and also supports artistic practice in the country.

Nubuke’s programming aims to “make the appreciation of art, culture, heritage and history accessible to all”. In 2017 the foundation extended its vision to support artisanal practice in northern Ghana by launching the centre in Wa as a space where traditional arts and contemporary art meet.

The exhibition consisted of three segments: a digital installation and two interactive opportunities – a pop-up exhibit and a “share your story” segment. The main audiovisual installation focused on history, chieftaincy, festivals and community life, themes that emerged from conversations with four regional chiefs.

In the participatory portion, visitors were invited to be a part of the story, to bring items that spoke of family histories, folk ways, festivals and the artisanal traditions of the area. These materials were arranged into pop-up exhibits.

Visitors also shared their reactions and memories via audio recordings, which were accessible on an MP3 player so that people could choose which story they wanted to hear or respond to, expanding the digital tapestries of histories while creating a culturally rich audio mosaic.

Soundcloud: hear Pamphilio Kuubesingn, a visitor at the Nubuke Foundation’s Clay and Textile Centre in Loho, Wa, during the Tapestries of History exhibition and participatory storytelling project in April 2018, telling us about the Nandom chief Naa Polkuu Kongkuu Chiir VI

The exhibition book incorporated some archival documents and photographs that loosely mirrored the themes of the digital installation. It was here the “unknown” chief was featured. And it was in this inclusive space of communal remembering and sharing that he was named.

As I listened to a visitor share not just the name of the chief, but his intimate memories of him, I saw clearly how important such participatory frameworks in Black memory spaces were. Eventually, I may have found the chief’s name, Naa Polkuu Kongkuu Chiir VI, in the archives, but would they have yielded these insights of him as a father?

As a historian and archivist of the African and African diaspora experience, I am acutely aware that silences, inadvertent and deliberate, loudly punctuate the telling and retelling of our stories. In the heritage space, I constantly ask: what are the stories we want to remember or tell? The silences we can’t allow nor afford? But submerged stories such as that of Naa Polkuu Kongkuu Chiir VI made clear to me that these questions are crucial.

In the continental African context, heritage workers must be sensitive to the possibility of silencing and erasure along class, ethnic or regional lines. Thus, even as I appreciate and stand in solidarity with the Black British Museum’s concern that “future generations see the relevance of their history, ancestral labour, and heritage in the making of Great Britain,” I must reflect on how I can ensure that future generations from marginalised regions will feel included in our national narrative.

I came away from that moment with a strong conviction that synergism across and between Black galleries, libraries, archives and museums, sector professionals and the communities we serve could best open up panoramic views and accounts of our stories. Indeed, it seems to me that this would offer interesting breadth and context to them.

Speaking as one whose academic work has looked to African and African diaspora rituals as alternative archives where buried stories could be excavated, such an approach could approximate the multi-sensory ways that African/diasporan communities frequently choose to remember.

Creating national holidays to mark major events in Black history is an important step forward

Bell Hooks, the American author, professor and feminist, once said: “‘Talking back’… is the expression of our movement from object to subject – the liberated voice.”

It has been a watershed year because for the first time, in 2021, Juneteenth – the day that marks the emancipation of slaves in America, 19 June 1865 – has become a federal holiday in the US.

This new addition to the calendar has been celebrated by BlkFreedomCollective, a national Juneteenth initiative and collaboration between 10 of the nation’s premiere Black museums. The momentous day is bookended by Black Music Month, which is celebrated in grand style by the newly opened National Museum of African American Music in Nashville, Tennessee.

June also kicked off another new celebration called Civic Season. This is a powerful consortium of more than 100 museums, which feature a campaign of collections content and ideas that champion civic engagement activities for Generation Z, through the timespan of Juneteenth to 4 July, American Independence Day.

As progressive professionals who steward Black museum spaces and programmes for Black and brown audiences, these celebrations are stepping stones to collectively finding our liberated voice. They shine rays of hope to our visitors as they re-emerge from the despair of the Covid pandemic, loss of lives and intense upheaval in our cities and spaces.

Simultaneously, Black museums have taken on a debt of tears, as we strive to commemorate painful pasts – enslavement, segregation, lynching, redlining, genocide, urban violence, gentrification, mass incarceration and racial terror – and dark days from the recent uprisings in response to the murders that occurred during the summer of 2020.

Centring our thoughts on liberation through celebration, our society must admit the need for new holidays that serve many purposes, remembering the old ways, charting new paths of commemoration and celebration to vow “never again” in the face of victimisation.

We need new and nuanced holidays, created by the people and for the people; intentionally crafted and agreed on by consensus. Holidays of enduring significance and challenge that meet the needs of the current complexity and intersectionality of society.

Holidays of triumph and testimony where lived experience and resourcefulness trumps founding fathers celebrating excessive wealth and war. We need holidays in the vein of Juneteenth that bubble up from a groundswell of advocacy and celebrate freedom and community care.

Quite often in US history, the concept of liberation and the celebration of it among the Black diaspora has been deemed radical, because it counters the status quo and disrupts mainstream society. Liberation celebrations ruffle feathers of privilege and perplex those in power, who do not understand “why Black people can’t get over slavery?”.

As Black lives have to be fought for, protected and reaffirmed, the ripple effects of centuries of bondage, and eras of oppression perpetrating a trail of tears from the transatlantic slave trade until the modern day, haunts our silver linings of Black joy.

In a polarised society that shuns critical race theory and shows empathy for murderous vigilantes and cops who threaten our livelihoods, Black museums have cultivated havens of freedom, safety and community care, fuelling the spark of activism for a new crop of revolutionaries, academics, curators, creatives and seekers. Black museums champion unapologetic Blackness as a birthright and touchstone for new and nascent Afro-futures.

Community care is an architecture of practice that honours empathy, advocacy, and social responsibility in service of society. To enact community care, institutions can freely offer opportunities for neighbours and stakeholders to engage in conversation, utilise historical and archival resources as teaching tools or simply provide a space to convene.

Strong partnerships and collaboration with mission-aligned organisations that traditional museums tend to overlook, is key to growing and catalysing a movement of community care in museums.

Black museums are also vehicles for community care before, during and after the pandemic. They have become activist institutions by extension, fighting on many fronts, preserving stories, by archiving oral histories and primary sources, speaking out on social justice by commissioning art, dance, poetry, theatre, and presenting exhibitions and programmes.

They also have been declaring points of achievement and documenting pride of place in the cannon. Black museums often hold space for people of colour to recount our wins and find joy in the fullness of our identities, perspectives and generations.

Community care can flourish when museums acknowledge the importance of community members’ voices and create spaces for visitor interaction and feedback.

Our Black museums and cultural institutions have the mandate of outreach, in the midst of other business, as they boldly address current events, to enable a unique community care approach to every element of museum craft: exhibition design, curation, education, partnerships, programme planning, fundraising and development.

Museums featuring activist content and unorthodox community-driven approaches, offer audiences and our sector a valuable transformative benchmark, on how to be socially responsive to the needs of the community. This method stretches beyond the one-size-fits-all approach and inspires trust, interest and goodwill among boards, stakeholders and visitors.

Looking towards the future of Black museums between and beyond pandemics, we seek to complement not complicate our winning approaches and innovative practice. Continuing to hold space for the grief, the growth and the tense gravity of our lived experiences.

We want our voices and ventures to be heard and seen as we come out of the shadow of the margins and force our agenda as essential and mainstream. Black museums and those that steward them will continue to passionately convene and take up space when none is given.

We historically met our audiences in churches, offices, speakeasys and secret societies. Now we are making our presence felt online, through social media, digital outreach, Black Twitter, affinity groups and chats, as we channel the energy of our dissent for emergent strategies and resilient futures.

Community care in museums

Spaces of difference

- Sharing authority and creative making. Museums act as spaces for conveners.

- Using stories, art, history, ideas to connect museums to communities.

- Organisations strive to offer innovative and novel programmes, education initiatives and exhibitions through honouring common threads and amplifying humanity.

- Organisations offer embedded residencies, coming outside of their walls to learn, listen and live among the audiences they serve, and reflect their interests and identities.

Spaces of resistance

- Expanding interpretation and speaking truth to power. Museum spaces as activists.

- Building equity and anti-racism into programmes, partnerships and decolonising practices.

- Organisations become allies and collaborators, tackling tough topics, current events and exploring intersectionality and representation.

- Organisations authentically partner with community members, hosting forums around societal issues, and changemaking inside and outside the walls.

A 30-year mission to help museums address the absence of Black history

The Caribbean historian Elsa Goveia asserted in a 1959 exhibition that: “Shame about the past too often fills the place that should be held by knowledge. Knowledge of the past must play its part in our liberation from the bonds of the past.” Much of my work over the past three decades has been focused on helping museums address this.

For the Caribbean, replacing this sense of shame with a deepening sense of self-worth was, and still is to a certain extent, a key component of our agenda.

This initially happened at the Barbados Museum and Historical Society during the 1980s and was later expanded to the work I undertook at Caribbean regional institutions through the founding of the Museums Association of the Caribbean.

Ultimately, it broadened out to the international arena through various initiatives with Unesco, the International Council of Museums, the Commonwealth Association of Museums and other entities, most recently the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience.

In other words, we moved from the assumption of solely nationalised histories to the recognition that globalised contexts needed to be recognised if we are truly to know and understand our own histories.

As the cultural theorist and political activist Stuart Hall said: “Instead of thinking of identity as an already accomplished fact, we should think, instead, of identity as a ‘production’ which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation.”

This overturns the assumption of many museums that permanent exhibits can and do capture authoritative unchanging “permanent” histories.

So, why then do we need a Black British Museum when so much of the museum community is currently invested in decolonial projects that are felt to positively address the absences and silences of past inequity in UK museum spaces?

For one, we need only look at the fraught environment engendered by the 2020 publication of the UK National Trust’s Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, Including Links with Historic Slavery detailing the connections of 93 historic places with colonialism and historic slavery.

As Jamaican-born artist, curator, researcher and policy maker Rachael Minott has said: “The need to decolonise museums exists because museums were tools of colonial celebration during the colonial era and continue to contribute towards neocolonialism in the present.”

Essentially, therefore, the issue raises the fact that while British museums are places that represent identity, it is an unchanging British identity that does not easily give space to alternate or contested histories, and then only on a temporary basis.

If we are to better understand Britain’s past (and indeed its present and its future) we need to start recovering those “othered” voices and peoples as the best means of balancing out public understanding of Britain’s imperial and patriarchal past with a more nuanced story of the right of marginalised Black communities to being present and participatory in British history and culture.

In other words, the Black British Museum is essential because, as the late reggae star Bob Marley expressed it in Redemption Song: “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery. None but ourselves can free our minds.”

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.