Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

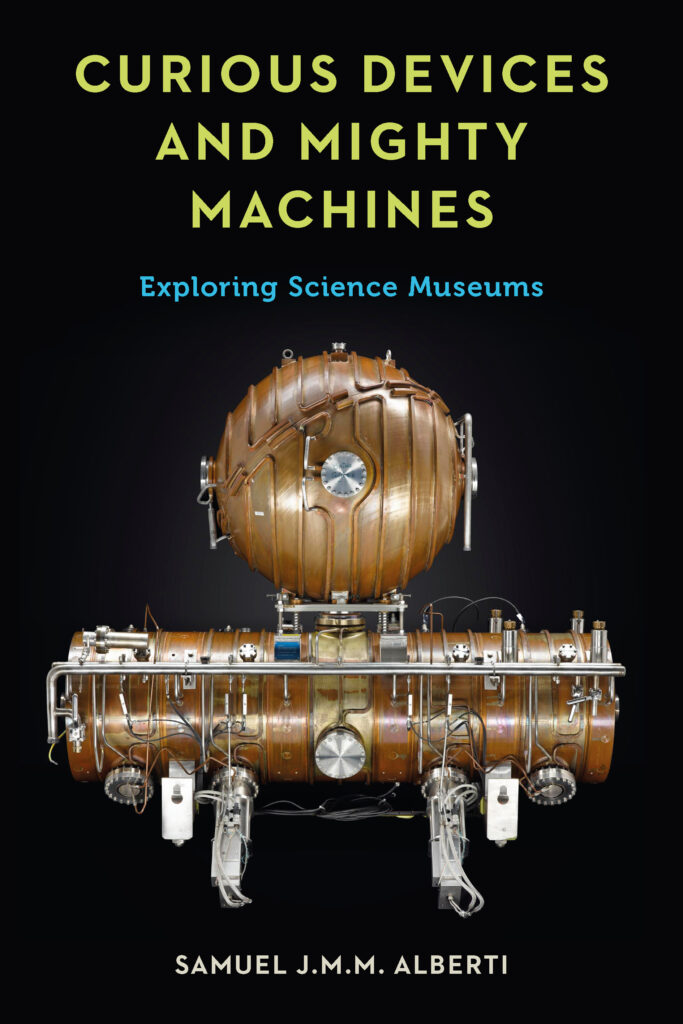

Picture a large copper machine covered in silver piping and wires. This image, which is on the cover of Curious Devices and Mighty Machines, could be a submarine or a robot from the golden age of sci-fi.

In fact, it is part of the Large Electron-Positron Collider at the nuclear research laboratory Cern near Geneva, retired in 1995 and donated to National Museums Scotland.

This intriguing science object serves to introduce Alberti’s book both visually and conceptually.

This is, by his own description, a “brazenly partial take on the function of science collections”, part of the emerging genre of curatorial tales made famous by Richard Fortey’s 2008 publication, Dry Storeroom No 1. Alberti’s book mixes a personal guidebook with a history of collecting and museological commentary.

Through five chapters, he looks at the history, purpose, use and future of science museums. Alberti starts from the premise that these institutions have “paradoxes” at their core.

They are both accessible and complex, historic and contemporary, focused on audiences and objects. He concentrates on collections in western Europe and North America, bringing out the similar aims and objectives unique to science museums: their mode of attention to audiences, with the use of “inspiring” in many mission statements; their collections, which require a blend of preservation and working use; their need to balance the past, present and future; and their focus on the relationship between science, society and culture.

Alberti uses a series of objects as a way into each chapter. These include the flare of a North Sea oil rig, genetically modified OncoMice to further research into cancer, a typewriter, a tractor and examples of nanotech.

Chapter one gives a brief history of how science museums came to be, highlighting how collectors’ and curators’ personalities have impacted collections.

Chapter two discusses how collections are put together, considering the balance of attention to be paid to historic and contemporary scientific endeavours by the curators.

Chapter three turns to the use of collections in research, making a heartfelt plea for the value of objects in store and their function as sources for both curators and external researchers.

Alberti argues for the equal importance of this smaller audience versus the thousands of visitors to science museum galleries, exhibitions and events, which are considered in chapter four’s focus on engagement.

Chapter five brings Alberti’s personal voice and passion to the fore with his plea for the advocacy role of science museums. He argues powerfully that science museums cannot be neutral, but “should be political, using their rich material memory and considerable credibility to campaign for good causes”.

The preceding chapters have served to demonstrate that museums have always been personal and political but can perform a role as trusted spaces with experts and objects, bringing the local and tangible to sometimes vague and global issues.

In part, this book does what museums do best. It introduces us to a series of objects, drawing us into their stories, why they matter, and what they can tell us more broadly about ourselves and the world.

Much like Alberti’s definition of science museums themselves, it is “a blend of gallery and playground… It seeks to inspire visitors (present and future) about science (past, present and future) and society… [through] science objects”. It does so with a pleasing range of illustrations although, alas, none in colour.

Yet, the book also begs the question of audience: Who should be reading this? The stories of objects and museum histories will appeal to the specialist and enthusiast.

Alberti’s own expertise in these collections shines through, but it is not the “behind-the-scenes” experience offered by others in the genre to the curious visitor. He makes some important museological arguments, but will these be read by the people who need to hear?

In essence, Curious Devices also demonstrates the paradoxes – the tension of historic and contemporary, accessibility and complexity, visitors and objects – that continue to challenge conclusions on what science museums today are for.

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.