Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

In 1972, a 35-year-old disability rights campaigner, Paul Hunt, wrote a letter to the Guardian newspaper inviting others to join him in forming a union against segregated living and disability discrimination.

Hunt lived with a degenerative physical impairment and had spent much of his life in residential institutions. Inspired by the civil rights movements of the 1960s, he became a leading figure in the nascent liberation movement for disabled people.

Hunt and fellow campaigner Vic Finkelstein went on to co-found the Union for the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) – the organisation that kickstarted the UK’s disability rights movement.

Disability facts and figures

- 16 million disabled people in the UK

- 11% of children are disabled

- 23% of working-age adults are disabled

- 45% of pension-age adults are disabled

Source: Family Resources Survey (2021-22)Access survey of UK venues

- 72% of disabled visitors have found accessibility information on a venue’s website to be misleading, confusing or inaccurate

- 74% of disabled visitors have experienced a disappointing trip or have had to change plans due to poor accessibility

- 91% of respondents try to find disabled access information about a new place before visiting

- 58% of survey participants avoid going to a venue if it has not shared its disabled access information, as they assume it’s inaccessible

Source: Euan’s Guide Access Survey 2022

Although Hunt died in 1979, the movement in which he had been pivotal continued to gather momentum. UPIAS formulated the key principles of what was to become known as the “social model of disability” – the recognition that disabled people are primarily impaired by the barriers imposed on them by society.

In a world where disability was viewed through a medical lens – as a problem in need of fixing – this was a revolutionary concept.

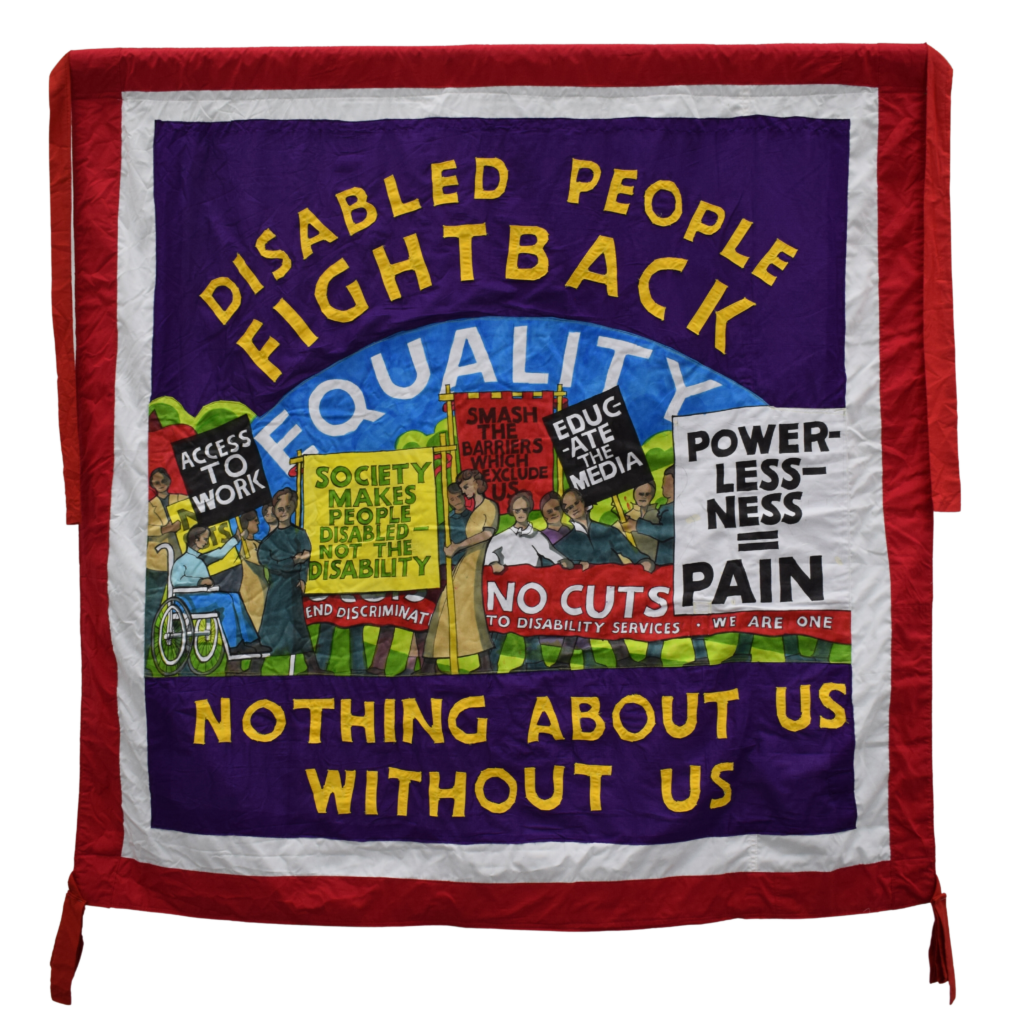

Art and culture soon became an integral part of the movement: disabled practitioners such as the artist Tony Heaton, musician Ian Stanton and comedian Barbara Lisicki challenged preconceptions and introduced anti-ableist ideas to the public realm through their provocative, irreverent and groundbreaking work.

This activism culminated in the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA), which passed in 1995 amid optimism that times were changing. But while legal protections for disabled people were strengthened and physical accessibility improved, the cultural change that was hoped for did not follow.

Disabled people remain excluded, under-represented and unequal at every level of society, and ableism is still pervasive and widely tolerated.

The Equality Act of 2010 subsumed the DDA, strengthening harassment protection and imposing a duty on employers and service providers to ensure equal access and representation. But campaigners feel that this legislation has proved toothless and that disability has fallen off the political agenda.

In some ways, things have gone backwards for disability rights: a decade of austerity wiped out many gains. Disabled people were demonised and dehumanised by the media as some politicians became intent on making life as difficult as possible for benefit claimants in order to justify spending cuts.

Then came a pandemic that saw mass redundancies, setting disabled representation in the workforce back years.

People with clinical vulnerabilities or mobility issues were forced to endure months and even years of isolation. Support networks vanished and accommodations for anyone with different needs were put on the back burner in the ensuing upheaval.

These setbacks have played out in the museum and heritage sector as much as everywhere else. Disabled heritage is not widely protected or collected, and disabled expertise is often lacking in organisations.

Meanwhile, the sector itself is still structured around ableist thinking; museum narratives tend to focus more on what has been done for disabled people in the past, and less on how they have contributed to society.

Even physical access is far from perfect: a survey by the disabled-access charity Euan’s Guide found that in 2022, 74% of disabled visitors had experienced a disappointing trip to a venue or had to change plans due to poor accessibility, and 72% had found accessibility information on a venue’s website to be misleading, confusing or inaccurate.

However, there are pockets of change. The £1m National Disability Arts Collection and Archive opened a repository in 2019 to preserve and celebrate disabled culture and the history of the disability rights movement. Disability-led organisation Shape Arts runs the archive and continues to build its collection.

Leicester University’s Research Centre for Museums and Galleries is a leader on rethinking disability representation.

Its Everywhere and Nowhere programme – which uncovered hidden disability histories at National Trust properties – has resulted in new guidance on ethical and inclusive ways that museums can research and interpret stories connected to disability and the lives of disabled people.

The charity Accentuate’s Curating for Change programme is pioneering inclusive recruitment practices to increase workforce representation.

Innovative research is also taking place. The Disability in British Art network was set up last year to address the historic absence of disabled artists and exclusion of disability as an artistic subject.

Meanwhile, the Sensational Museum has launched to rethink the role of the senses in museums, with the aim of moving away from segmented accessible provision for disabled people towards interventions that work for everyone.

Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and working with partners such as the Museums Association (MA), the two-year initiative aims to develop a new “sensory logic” in all aspects of museum work that does not privilege access through any one sense.

It is hoped that this research will enable the Sensational Museum to put disability at the heart of museum practice.

Ultimately, an overarching plan of action for the sector is needed. This autumn, the MA, in partnership with key individuals and organisations, will launch a campaign that aims to support museums, and those that fund and work with them, to work in an anti-ableist way.

But real transformation won’t just happen: it needs leadership and support from individual museums, sector policy-makers and political leaders.

In the half century since the disability rights movement began, much has been written and discussed about disabled access and representation in museums. It’s beyond time to turn words into meaningful action.

This article was informed by research from the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive

Ableism in museums: workers share their experiences

“I was asked to prove I was disabled when asking for the concessionary price to get into a gallery. I said that I thought arriving in my own wheelchair might have been proof enough. I was told it wasn’t and I needed ‘official’ proof like a letter from a doctor. The people behind me in the queue were uncomfortable, particularly when I offered to drop my trousers and show them my clearly non-functioning legs.”

“My manager said he couldn’t show me a lighting system as it would set off my epilepsy. I said I am not photosensitive. He continued to argue with me, getting increasingly frustrated as he explained my condition to me (incorrectly).”

“The only disabled toilets in the staff area are behind three fire doors – which require two hands to open. I use a walker – which uses two hands. The math ain’t mathing, as they say.”

“A woman once asked her friend why her ‘taxes were being used to pay the salaries of cripples and retards’, while waiting to buy tickets from me.”

“I can often forget things, so I prepped lots of notes [for a job interview]. The interview was with someone who knew of my reasonable adjustments. It went well and, as they flipped through their pages of questions, I scanned my single page where necessary to remind myself of points I wanted to make. I got told immediately afterwards I hadn’t got the role. Apparently, using notes during the interview was an automatic disqualification. I had spent more than an hour talking, having already lost the role.”

“I have had feedback from an organisation that I seemed ‘nervous’ because of my animated presence, and ‘oversharing’. I was advised not to do this in future interviews. These are not character traits I can work on, but autistic traits I would have to mask. It read ‘be less autistic if you want a job in this sector’.”

“There are so many tokenistic participatory projects in the sector. Over the years, I have found that many well-meaning museum workers have taken the time to reach out to me to tell me all about their projects, how committed they are to listening to disabled voices, and what a difference I could make if I were to get involved. What they don’t often tell you – and hope you don’t ask about – is whether you will be paid for your time and the likelihood that your contribution will result in meaningful change. It can feel like box ticking at best; at worst it can feel like they wish to take your work and make it their own. There is an expectation that your lived experience – your expertise – should be contributed for free, and to not take part is selfish or missing out.”

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.