Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.

The American Museum of Natural History was created during the grand era of the founding of museums, more than 150 years ago. The plan was for a continuous campus across four city blocks, a vision that has been brought up to date with the opening of the Gilder Center.

This enormous project, designed by architecture firm Studio Gang, features galleries, a vivarium, insectarium, library and learning centre, a collections centre that offers three stories of floor-to-ceiling exhibits, and a large immersive experience called Invisible Worlds.

But the Griffin Atrium is the jewel in the crown – a soaring yet inviting space that opens out onto Theodore Roosevelt Park. The atrium sucks natural light and air into the building’s interior, while stone cladding, deep-set windows and tree-shading further cool the building aiding its sustainable credentials.

The building’s curvy concrete walls were formed using a technique known as “shotcrete”, created by the museum’s former employee, the naturalist and taxidermy artist Carl Akeley (1864-1926). His technique involves spraying fluid concrete onto an underlying structure, rather than casting sections.

The hope is that the Gilder Center’s huge spaces will support a pre-pandemic annual attendance of five million, while nurturing an increased sense of planet-wide connection.

Here, Lauri Halderman, the museum’s vice-president for exhibition, shares her thoughts on conveying commitment to conservation through the lens of wonder and curiosity.

Lauri Halderman: In this country, studies have shown that museums are trusted more than governments. This is acutely relevant when information is so challenged – whether about the pandemic or climate change.

We are viewed as places where information that isn’t “fake news” can help you make decisions in the real world. So, we wanted to bring the scientist’s task of asking questions and deciphering answers before the public. And we wanted visitors to be inspired by our transparency, to ask themselves more questions about the world using reliable evidence.

Connection is our defining theme, as well as our planet’s reality. Connections occur continuously, although their scales aren’t always apparent – some are microscopic, some as big as the universe, some are as quick as neurons firing, some as slow as trees growing.

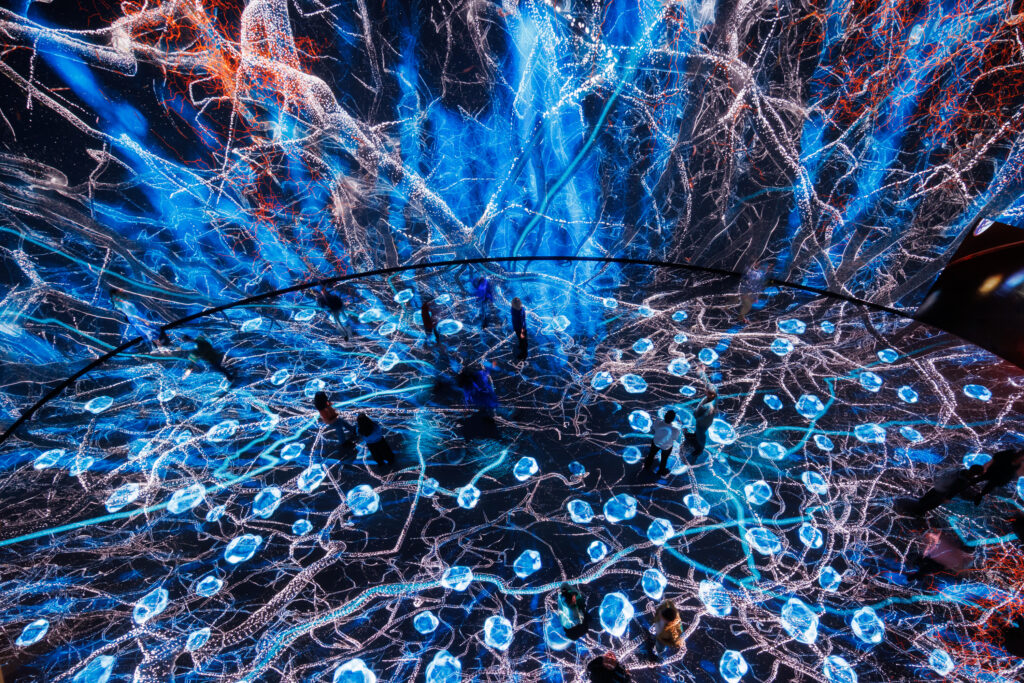

But if we are to survive, we need to understand and appreciate this continual state of connection. The Invisible World Experience is a looping, 12-minute, 360-degree immersive show exploring this. A pre-show exhibition presents connections through DNA, ecosystems, food webs and communication.

Then, in a hockey-rink-size space, visitors are surrounded by high walls, projections of all scales, and wall-to-ceiling mirrors representing infinity.

They witness the building blocks of DNA, ecological connections in forests, oceans and cities, and communication made possible by trillions of connections in the human brain.

At moments, visitors’ own movements affect and interact with the images of living networks, encouraging an understanding of their connection. We don’t want to beat people over the head with conservation messages, but we want them to love the natural world so that they care about it.

The minute you enter the physical space, you’re in awe. The undulating, canyon-like space has been built to invite exploration and discovery.

The building makes connections to the fact that people are connected to the natural world. Visitors might not necessarily grasp all that when they first step in, but the construction and layout definitely offer a sense of wonder and curiosity.

The gallery plays with seeing insects differently at different scales. In addition to two huge models of plants with flowers, more than 60 oversized honeybees “fly” from the eastern end’s pollination portal to the western end, escorting visitors on their way.

Crucially, at the huge hive at the western end, visitors make connections between pollination and food. Hives, with their unseen tasks and roles, are a good metaphor for a museum ecosystem.

The insectarium, definitely. With digital displays and hands-on models, we’ve worked hard to reinvent an insectarium’s possibilities. Visitors can pass under a sky-bridge containing one of the world’s largest live leafcutter ant displays and be in a sound gallery with the “melodies” of insects from nearby Central Park, with the option of feeling the insect’s vibrations.

The Collections Core exhibit is an awe-inspiring glimpse of what the natural world can offer. Glass panels provide views into working collections areas at the centre.

Spanning three floors, all of the museum’s collections are represented, from vertebrate and invertebrate biology, palaeontology to geology, anthropology and archaeology.

Pueblo pottery sits beside Mayan bricks decorated with centuries-old doodles, and prehistoric trilobites can be seen beside ammonite fossils. It’s a reinvented cabinet of curiosities.

Rebecca Swirsky is a freelance writer

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.